Voters have a chance on March 29 to turn the tide against Gov. Jeff Landry and his legislature’s extensive, expensive plans to expand the criminal-justice system in Louisiana, which already incarcerates more people per capita than any other state

by Bruce Reilly February 18, 2025

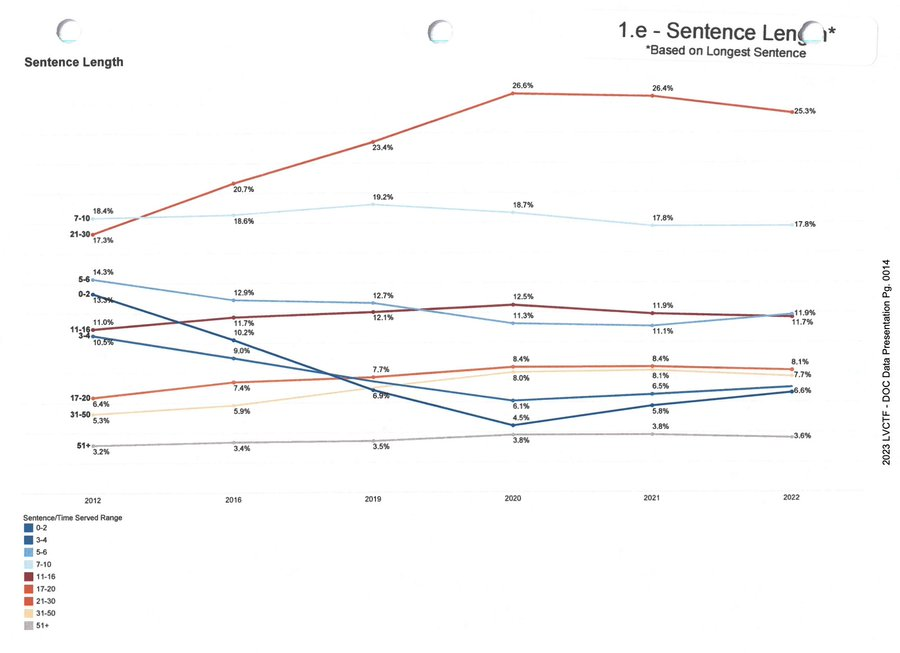

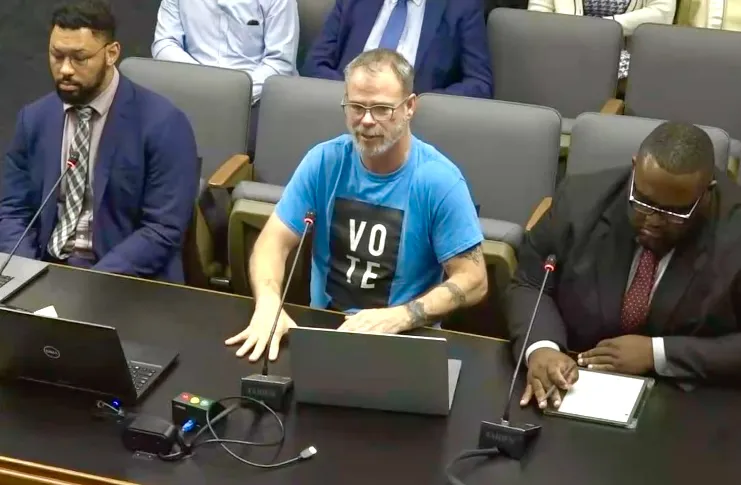

Bruce Reilly, center, with attorneys Claude-Michael Comeau and Hardell Ward from the Promise of Justice Initiative, testifying before the Louisiana Senate’s Judiciary C Committee committee about retroactivity for people convicted by non-unanimous juries. (Photo courtesy of Bruce Reilly/VOTE)

On top of what Louisiana legislators have done so far, they have more harms in store.

Right now, the best way to combat these efforts is to go to the polls on March 29, to vote down constitutional amendments that will send more people to prison and expand an already-oversized criminal-justice system.

Gov. Jeff Landry’s appointees are also putting other pressures on the system. Late last year, Louisiana’s newly appointed Secretary of Corrections, Gary Westcott, sent a letter to Orleans Parish justice leaders, pressuring them to send more people into his custody and control.

In a Dec. 3, 2024 letter, Westcott makes a “strong recommendation” for Orleans Parish District Attorney Jason Williams and Judge Tracy Flemings-Davillier to reevaluate their sentencing practices.

Westcott provided no specific data nor cases, no reasons why Orleans sentencing needed adjusting. Instead, he was vaguely referred to “violent offenders” and insinuated that, when faced with probation violations, the Orleans Parish District Court does not “take seriously a motion to revoke if filed by our probation officers.”

It is unclear if the letter, which also shares the governor’s name on the letterhead, is intended to infringe upon the constitutional power of the elected judiciary or elected district attorney. It has also been established thus far in the Landry administration that the governor will use budgets to reward or punish recipients of funds. To date, it’s unclear exactly what Orleans officials are being asked to do and what price they could pay.

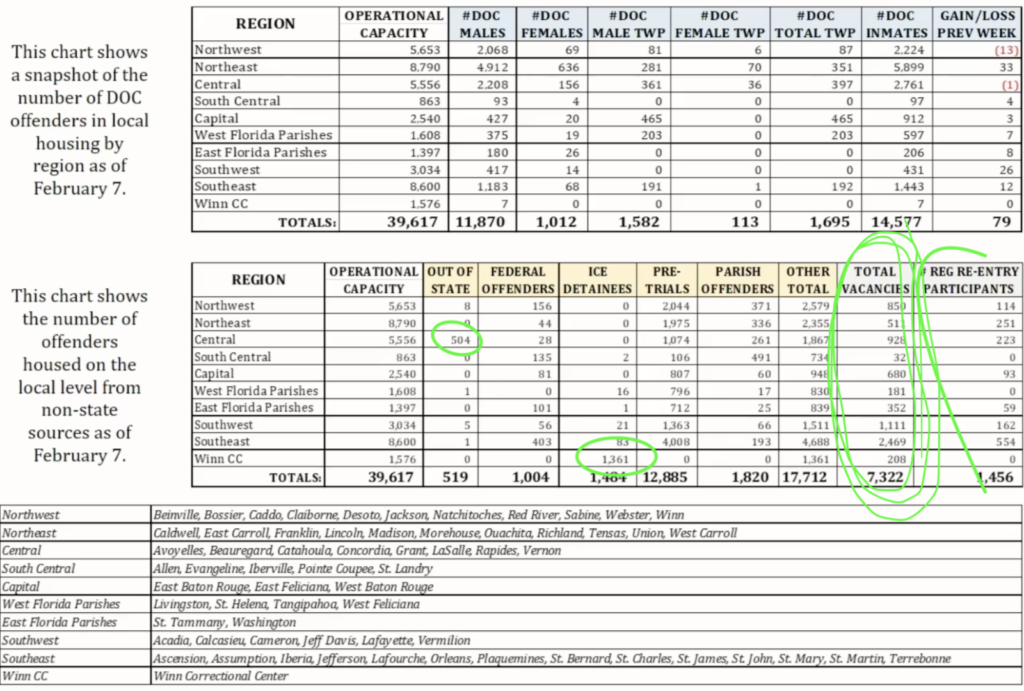

But even if Westcott disagrees with a handful of Orleans case outcomes that didn’t send prisoners his way, it’s safe to say that his prisons – and the jails that keep half of state prisoners – will not lack for occupants in coming months.

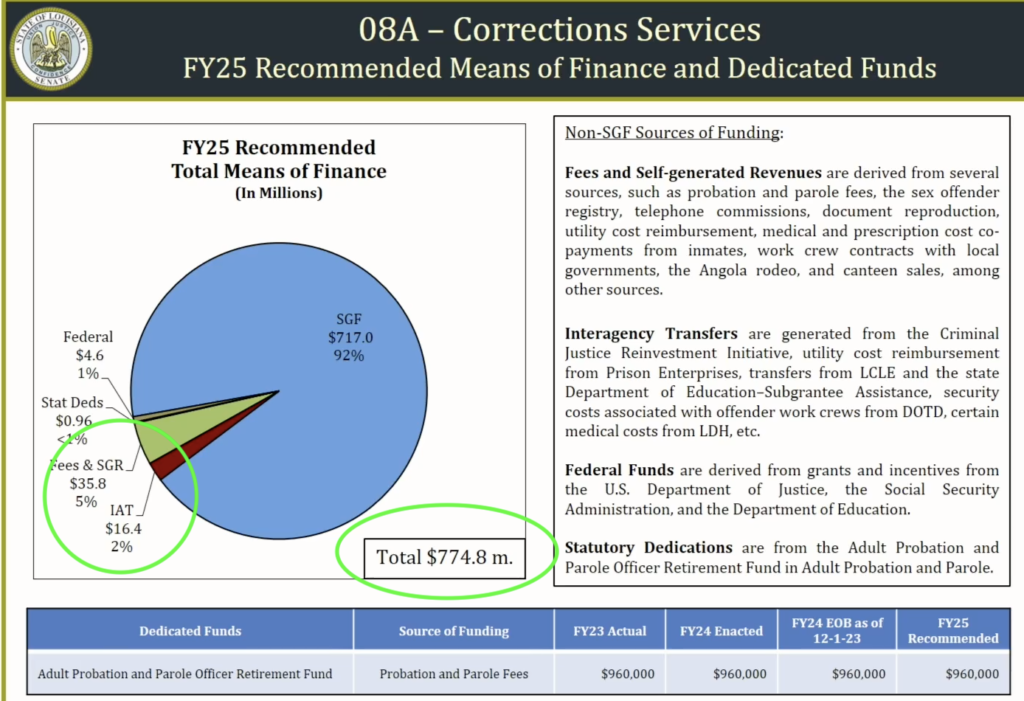

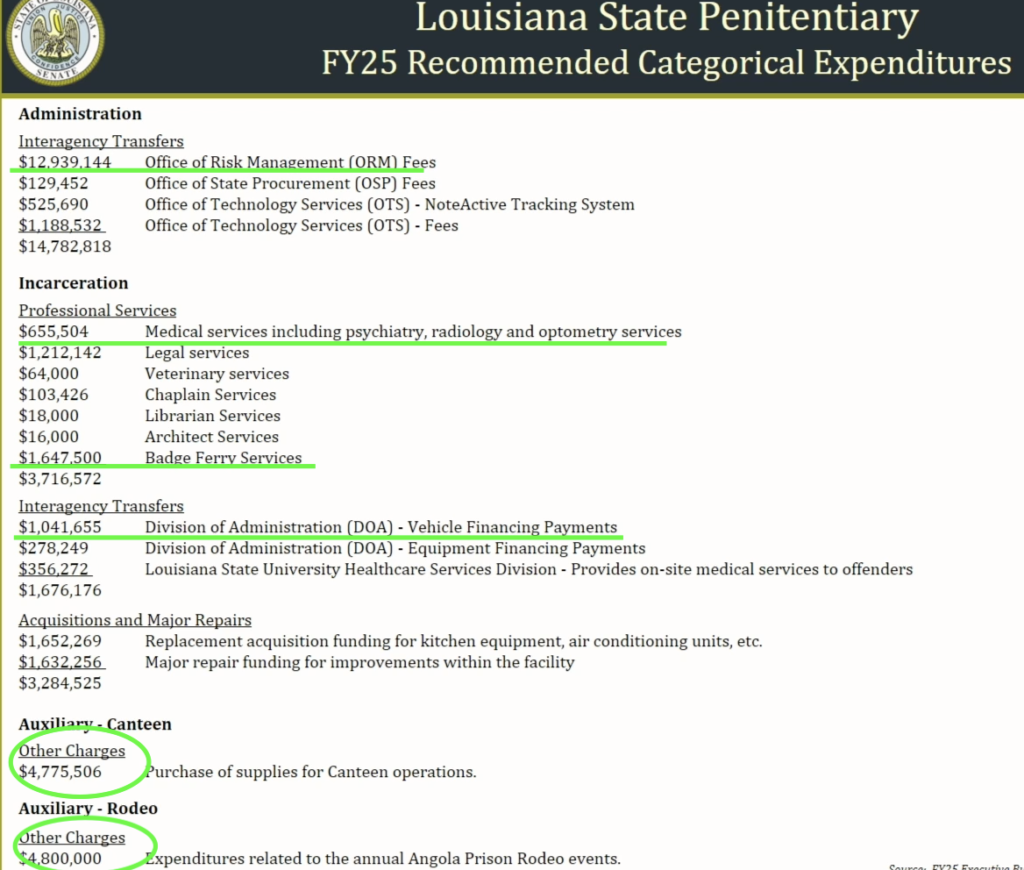

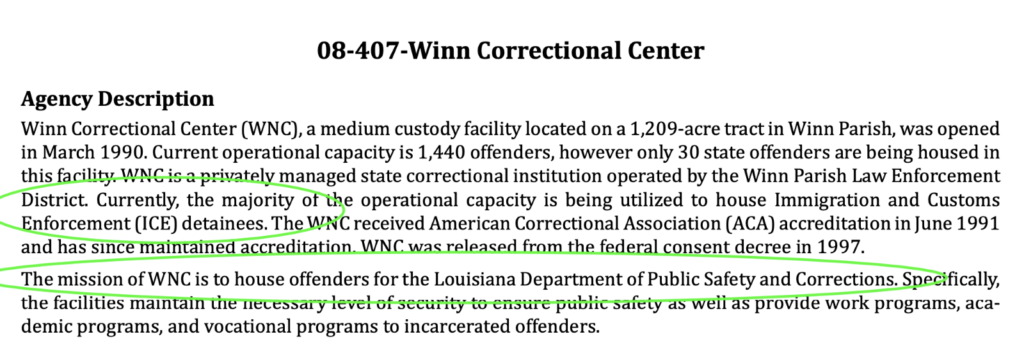

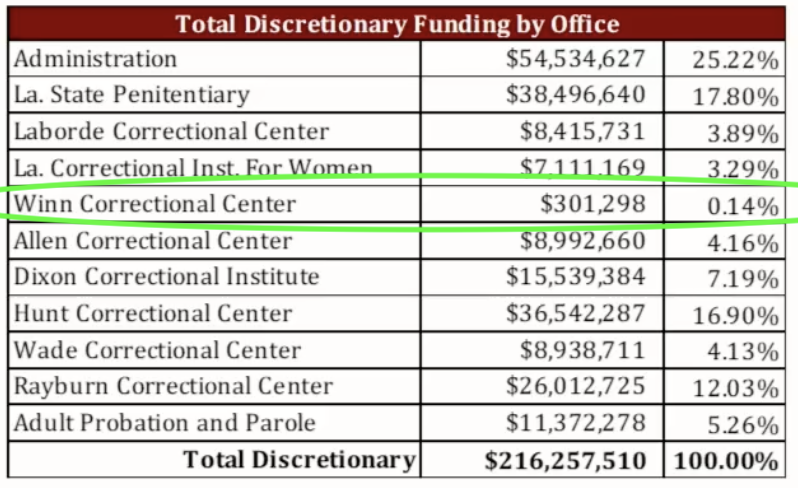

Soon, sheriffs’ coffers will likely be replenished with federal per diem money, as the Trump administration builds on its prior mass detentions of immigrants, which led to the detention of more than 10,000 people in Louisiana.

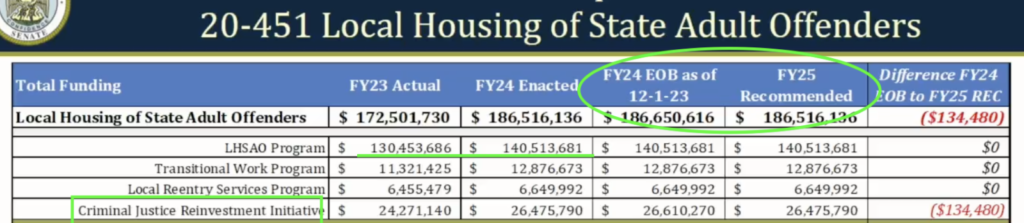

We can also anticipate that Gov. Landry will seek federal dollars to help construct new prisons. Prior U.S. prison expansion in recent decades has been fueled by the Justice Department’s Bureau of Prisons and Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Considering the current rhetoric and the flurry of executive orders coming from Washington, D.C., bills that appropriate more money to corrections would come as no surprise.

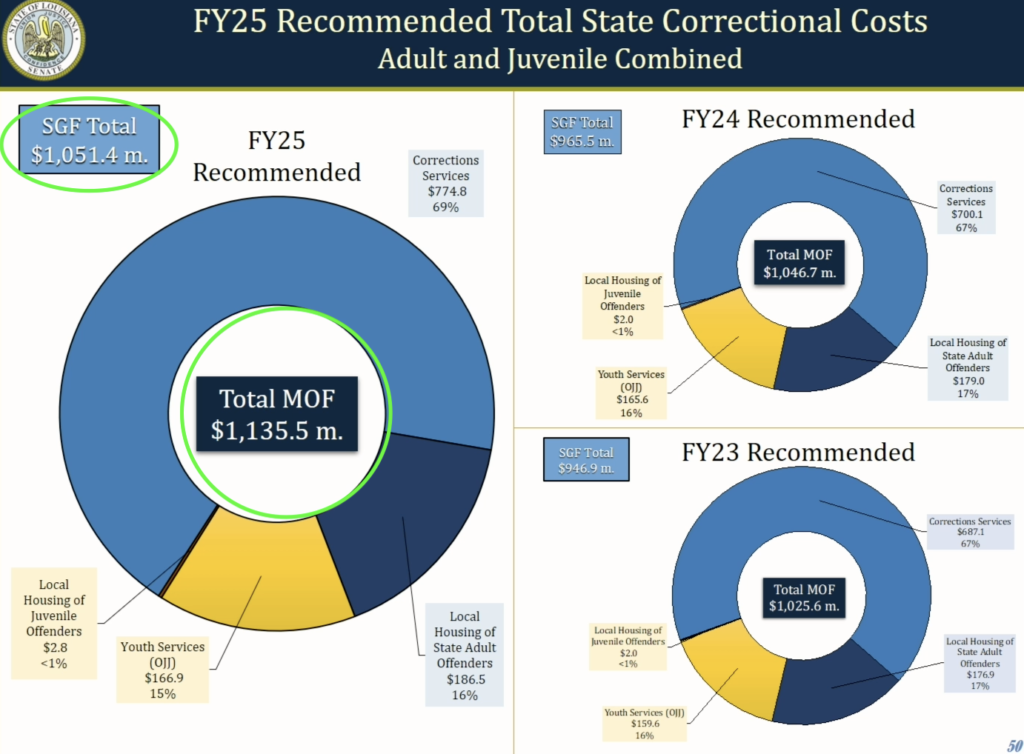

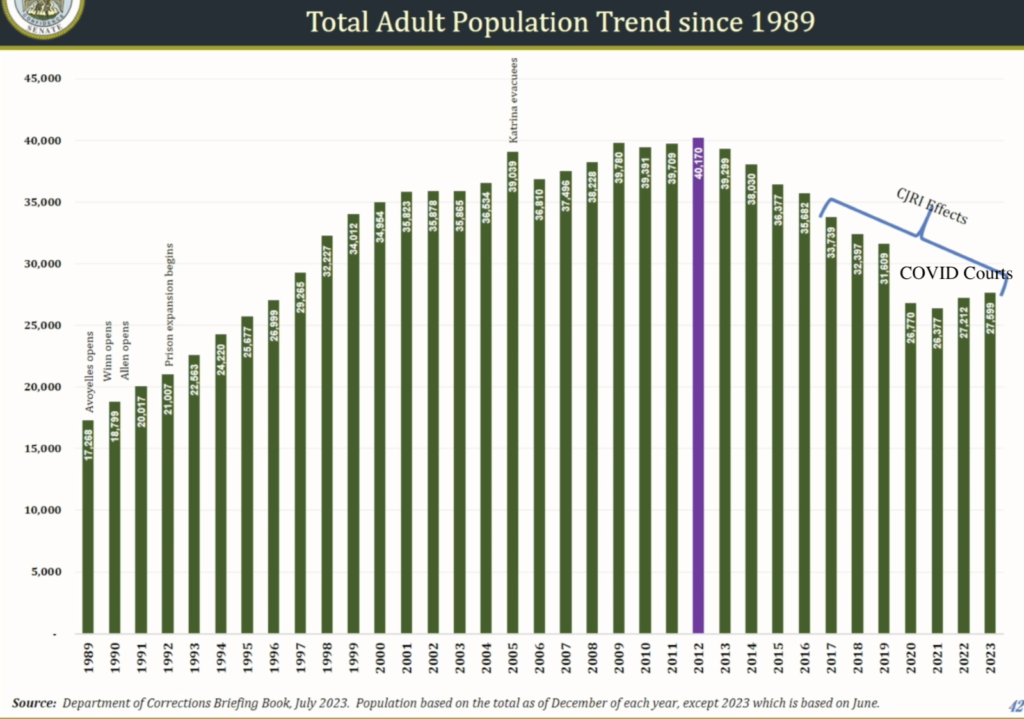

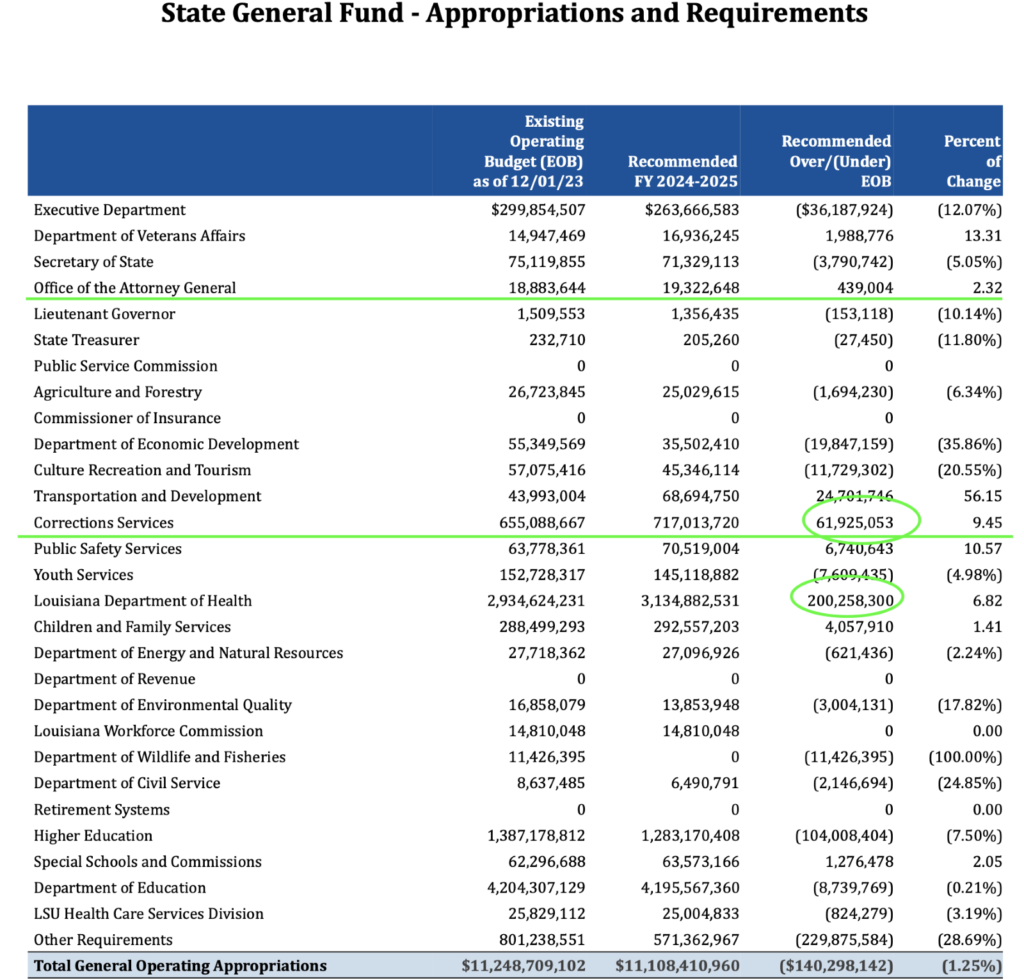

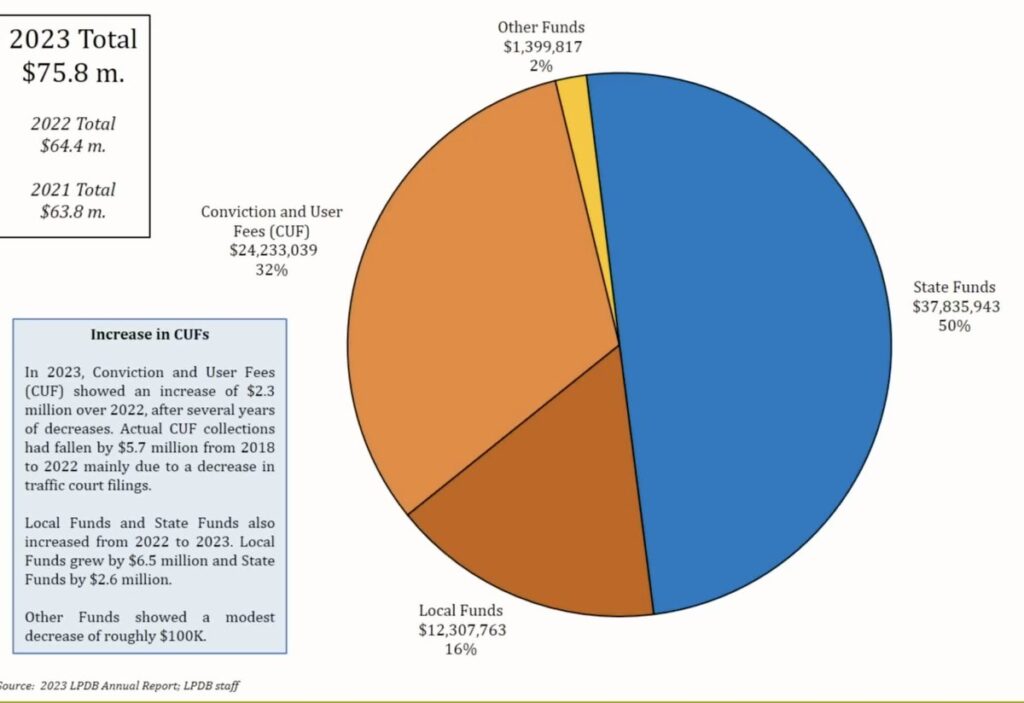

As you may have heard, Louisiana is already on track to double its prison population in six years, according to some experts. The foundation for the upcoming correctional-population explosion was laid early last year when Landry took office and, almost immediately, convened a legislative session focused on crime.

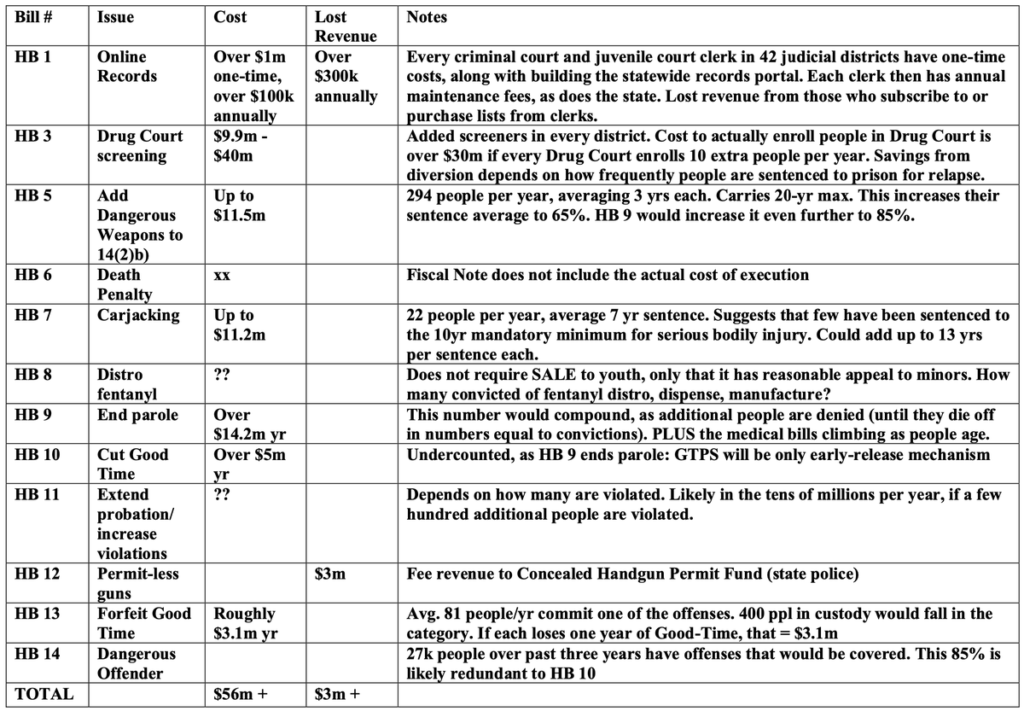

During that session, the legislature, working with the Landry administration, amended several key laws in ways that will fill our prisons and jails.

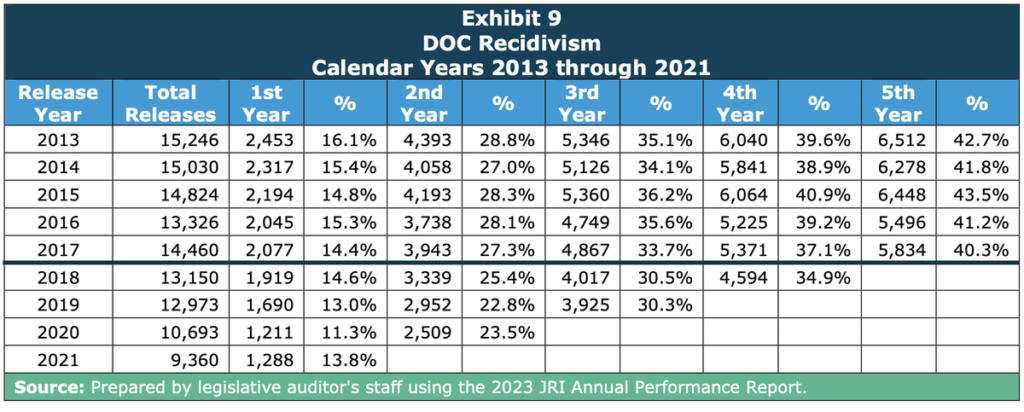

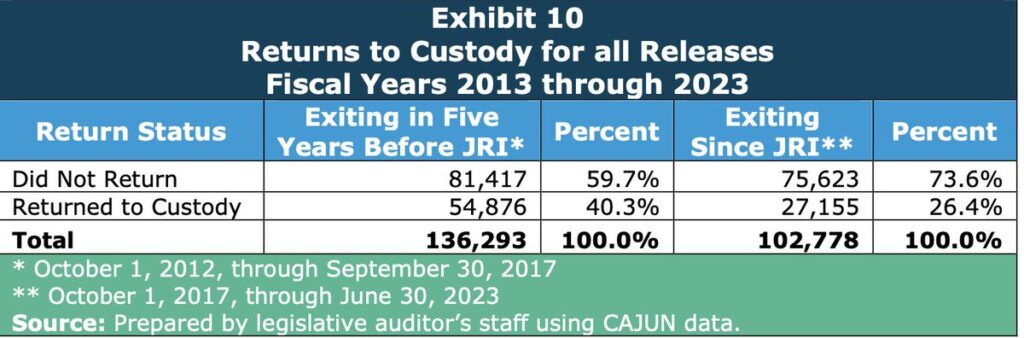

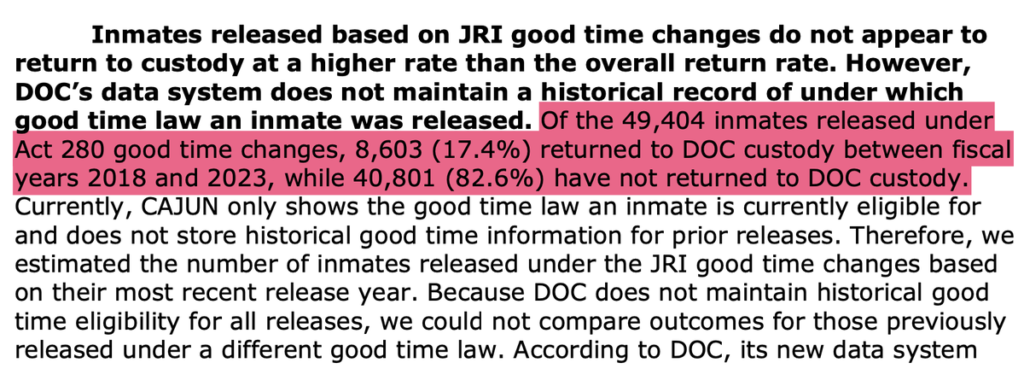

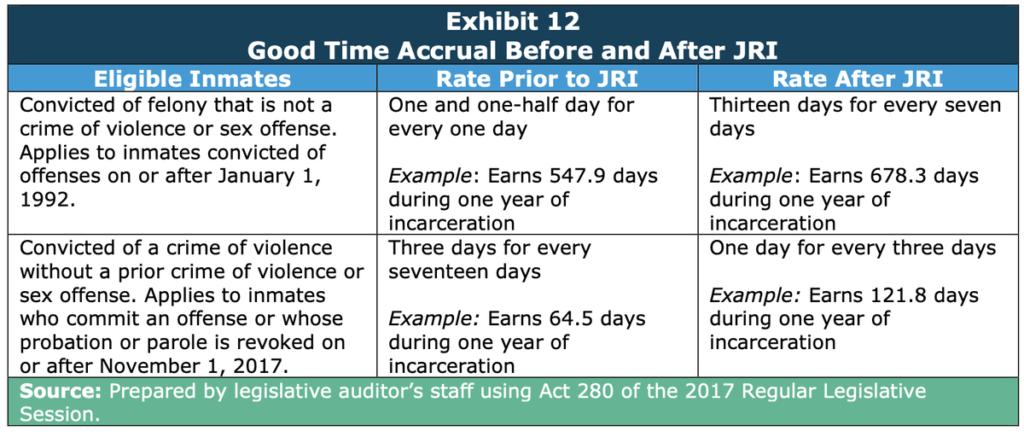

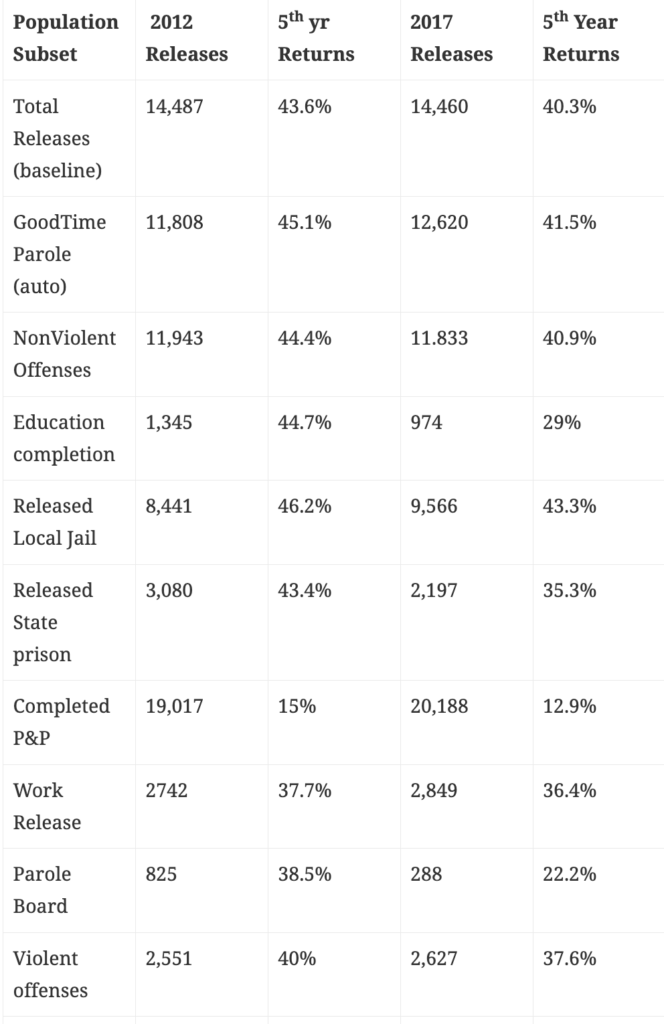

People on probation can now have their probation revoked for minor violations, sending them to prison. People sentenced to prison will stay there longer, because the state has ended Good Time credits and eliminated parole eligibility.

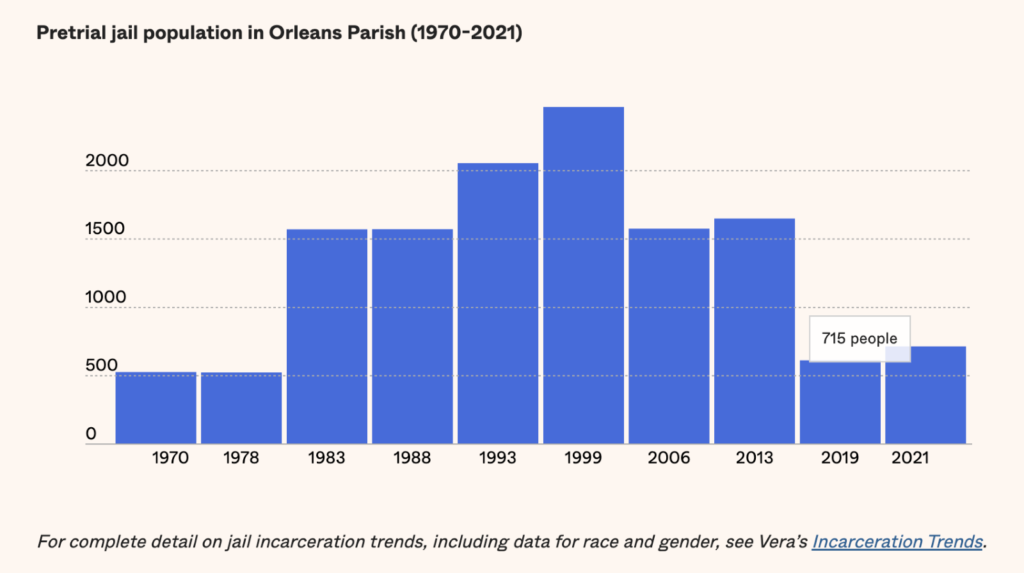

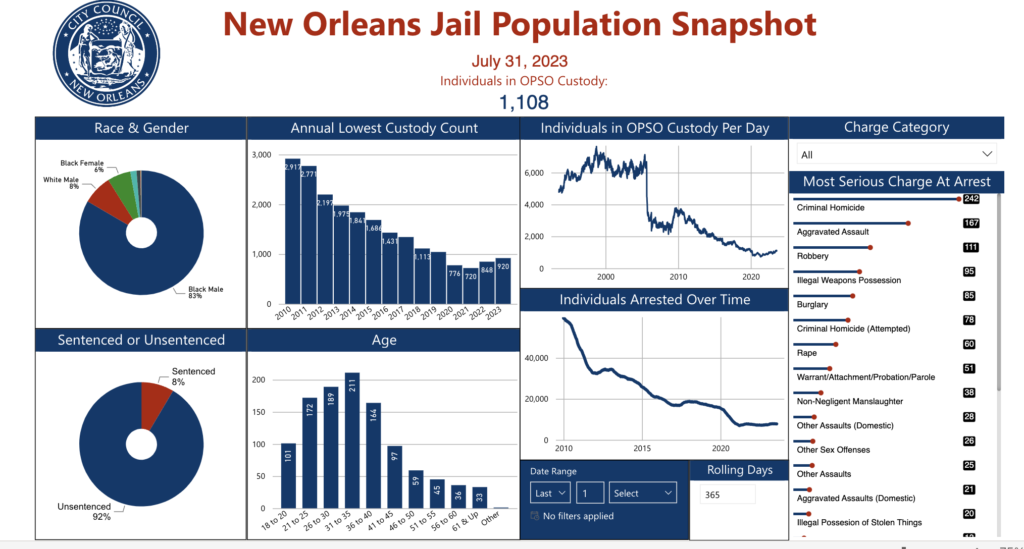

These punitive changes came as parish jails were already seeing large reductions in people behind bars, reflecting downward trends in crime that were apparent long before the governor’s crime session.

To stop the Landry-Trump machine, voters must turn out in force on March 29 to vote down all four constitutional amendments.

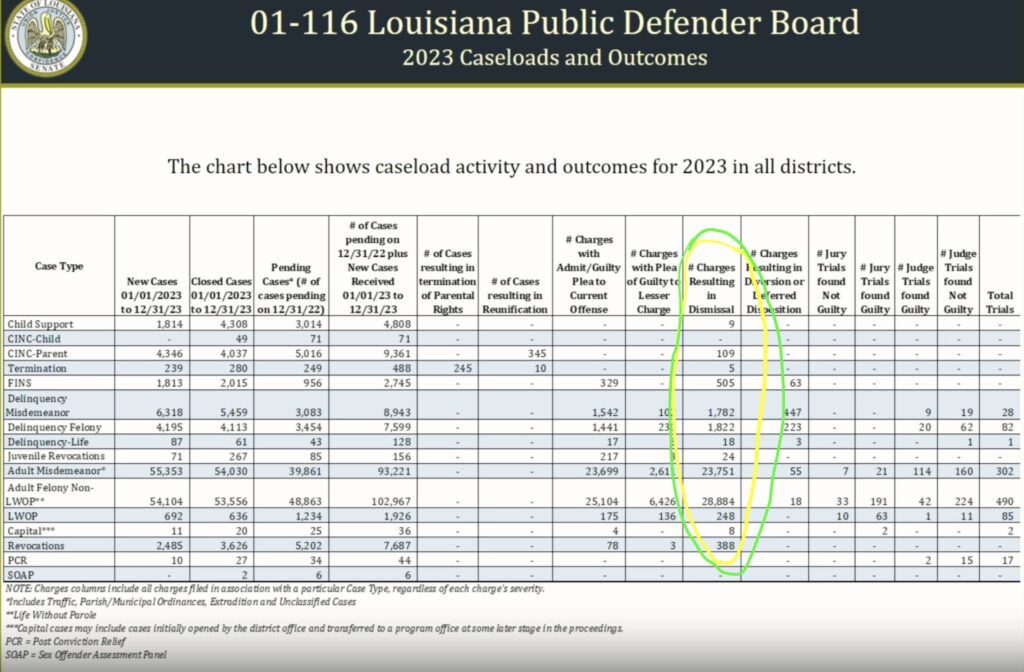

If not, Louisiana will be well positioned to further expand the jail and prison infrastructure. One proposal (Amendment 1, on the ballot) allows for the legislature to create new (“specialty”) courts outside the jurisdiction of the District Court structure, using appointed magistrates, and newly created procedures.

If this passes, every potential probation violation could go to a “specialty court.” They could also be destinations for every post-conviction writ for people who have been sentenced but who have claims of actual innocence, ineffective counsel, or judicial and prosecutorial misconduct.

With “specially” created court rules and a prejudicial standard of proof such as “reasonably satisfied,” Landry’s magistrates and Attorney General Liz Murrill’s prosecutors could bypass the democratic process of locally elected judges and district attorneys who are accountable to the community. Not long ago, news reports revealed that one of Louisiana’s appellate courts had systematically denied more than 5,000 petitions claiming wrongful convictions; something so common it didn’t even merit a scandal..

Other specialty courts could go beyond current standards of justice. For instance, there could be a “Right to Life” Court, where women are detained for the protection of their unborn children based on a “reasonable suspicion” that their health is in danger. Others who might land in such a court are people charged with transporting someone – even their own daughter – out of state for an abortion or those charged with assisting in the procurement of banned medications such as mifepristone, which is used in medication abortions. Anyone believing this to be a dystopian delusion has not been paying attention, as Landry has already tried to get the federal government to supply him with information about Louisiana residents who obtain out-of-state abortions. obtaining women’s private health records, and Murrill has charged – and tried to extradite – an out-of-state doctor accused of providing the mother of a pregnant minor with mifepristone (which is not illegal in New York, only in Louisiana and a dozen other red states).

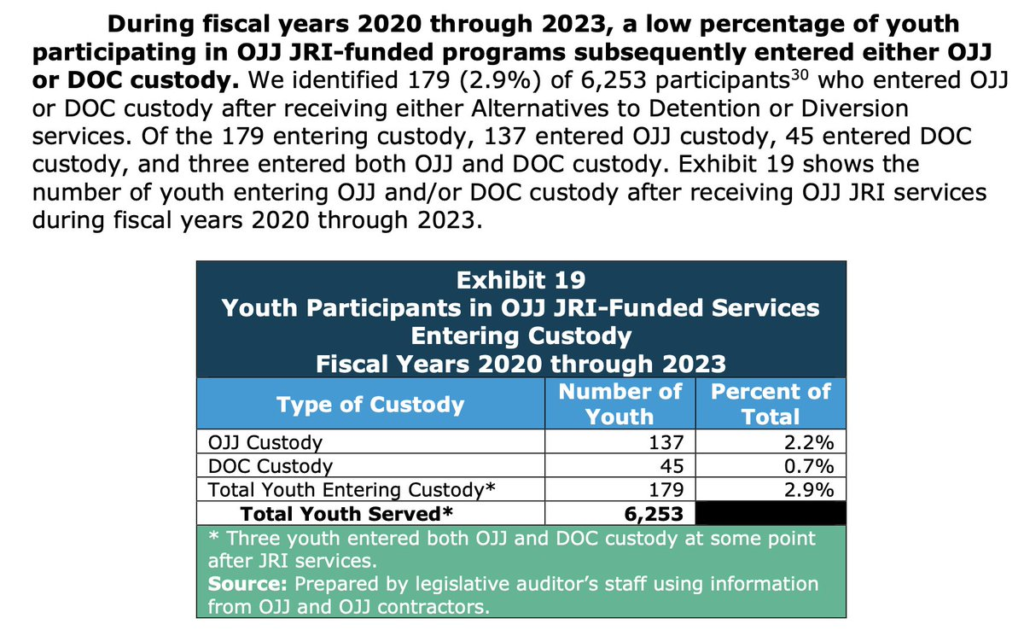

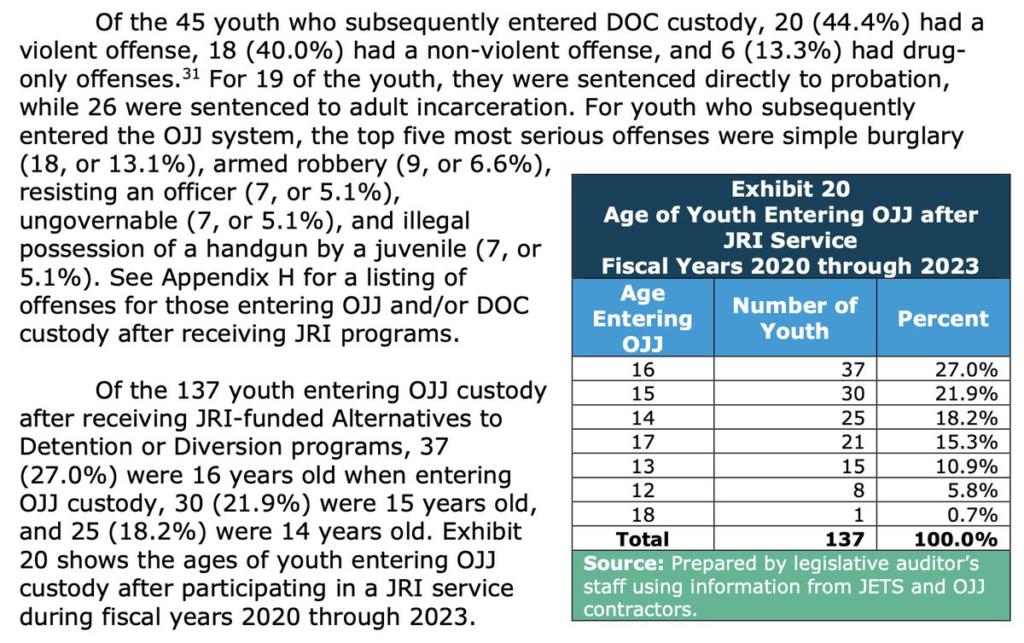

If Amendment 3, another constitutional amendment, passes on March 29, Louisiana is also likely to create a specialty court for children accused of violent crime. This would allow the legislature to create lengthy adult sentences for children.

Judging by what happened last year, legislators will pass a bill that allows a district attorney, on their own discretion, to try a child under the age of 17 in adult court for any of the 60 crimes listed in R.S. 14:2 (b) – and any crimes that state legislators want to add to the list. Children could be subjected to various mandatory minimums along with maximum sentences up to 99 years, without parole.

The state already has the ability to charge children under 17 as adults for the most serious of crimes, as outlined in the state constitution. But the legislative list of crimes includes, for instance, the distribution of “detectable amounts” of fentanyl, which carries a 25-year mandatory minimum. A 15-year old, even if unaware that his drugs have a trace of fentanyl in them, could be imprisoned until he turns 40.

Landry was voted into office by record-low voter turnout. Now, his current plans need to be shut down by voters turning out to send a strong message: over-incarceration and adult prosecution of teenagers does not work to prevent crime. In fact, it does the opposite: it destabilizes our communities and families, opening up doors for more crime.

Nothing is as promised on the March ballot. Even Amendment 2, which promises “teacher pay raises” but does not guarantee any additional funding for teacher pay – and cuts crucial seats from early-childhood programs that legislators already slashed by $9 million in June.

Voters should be very concerned when public officials aren’t willing to tell you the whole truth.

And, in an effort to push these amendments through as quietly as possible, legislators even cut corners with a new law that allowed these four amendments to be on the ballot on March 29th, an off-cycle election date that will attract few voters, rather than in the fall, as the law had previously required.

Have your elected officials from City Hall, District Court, the Legislature, or Congress contacted you about this upcoming critical election? If not, ask them about it. Early voting starts Saturday, March 15th. Election Day is two weeks later, on Saturday, March 29.

Bruce Reilly is deputy director of VOTE, Voice of The Experienced, which advocates for policies that address root causes of crime, curb incarceration and support people within jails, prisons, and communities.