Have you read the 2024 DOC Budget? We have. And we think you should too. Or at least some highlights. Snag our full 2024 DOC Budget Explainer, on our website: https://www.voiceoftheexperienced.org/s/2024_03-DOC-Budget-Explainer.pdf.

Our hope is to make the DOC Budget more transparent and accessible for our community including legislators, elected officials, media, reporters and investigators. We should all know where our tax dollars are and are not going. If our budgets are moral documents, let’s see where our morals lie.

****

THE INCARCERATION BUDGET: HIGH AND CLIMBING HIGHER

Budget documents are one of the best ways to cut through the chatter and get down to the numbers. What are we trying to do, and how much are we spending on it? From the time Gov. Jeff Landry ran for office to the time he celebrated his “special crime” legislation, one would guess a few things based on not just his words and deeds, but the people around him.

First, they believe that the way to prevent crime is to ensure someone is convicted, incarcerated, and not released for as long as possible so they can commit no more crimes (at least not until released). Second, they don’t believe in the concept of rehabilitation, change, second chances and helping people assimilate back into society. Finally, they are willing to write a blank check to achieve goal number one. With that said, it is increasingly difficult to understand the mission of the Department of Corrections if it reverts into a place of hopeless and brutal punishment that incites more crime than it prevents.

What follows is a look into the overall funding, a framing of the incarceration industry as a Louisiana employer, and the peculiar usage of local jails to handle a state obligation. Download the full budget here.

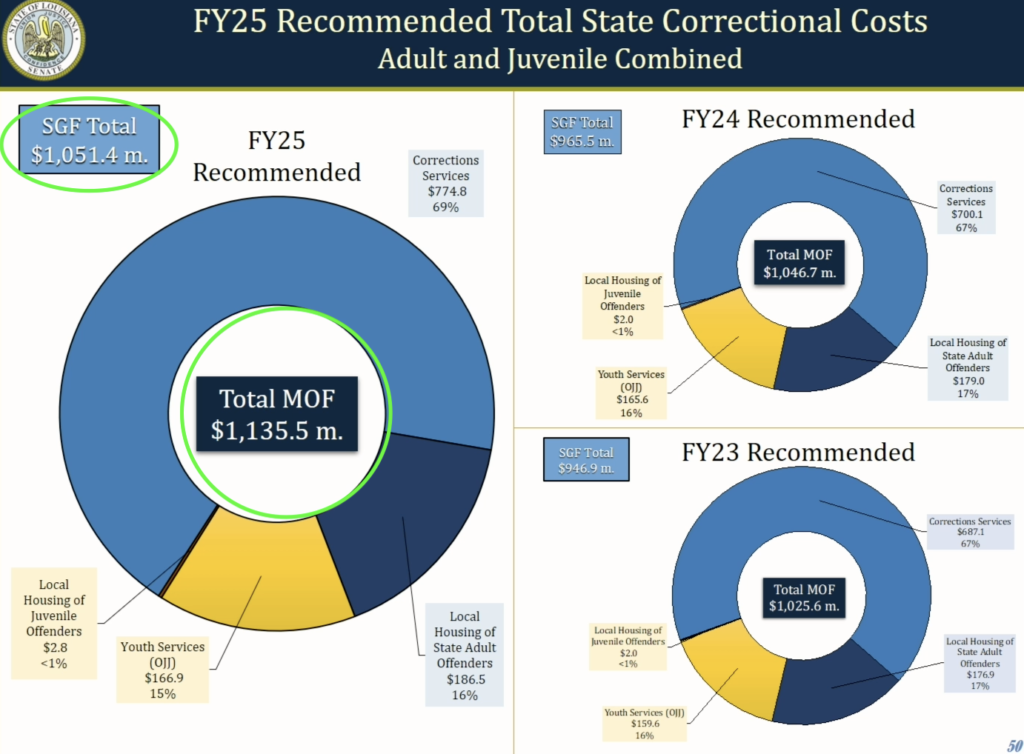

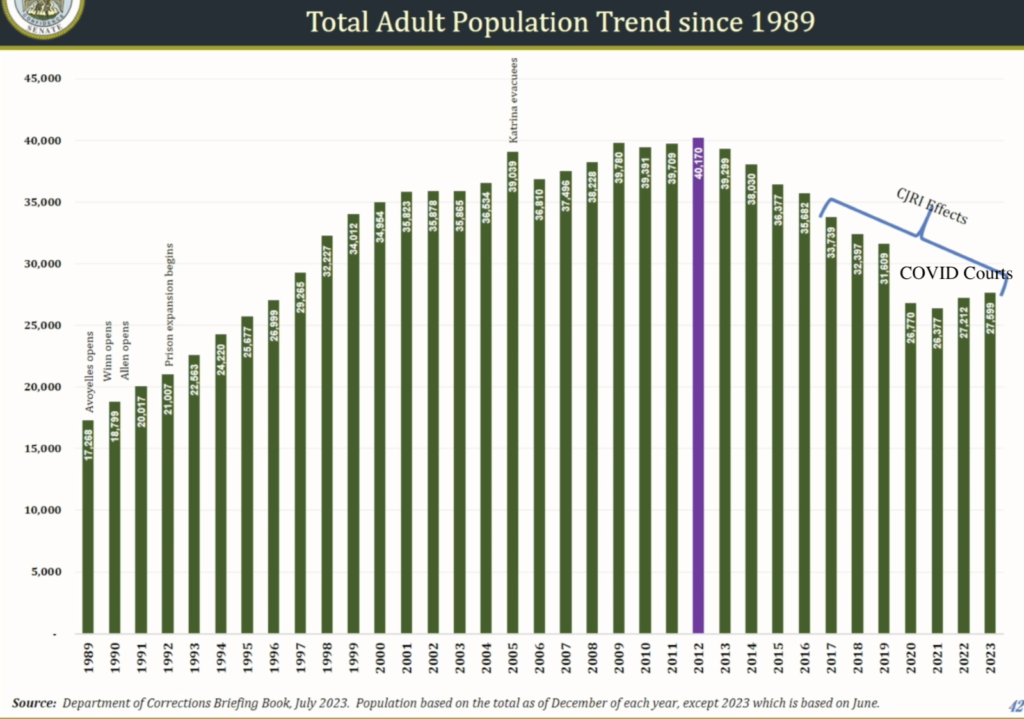

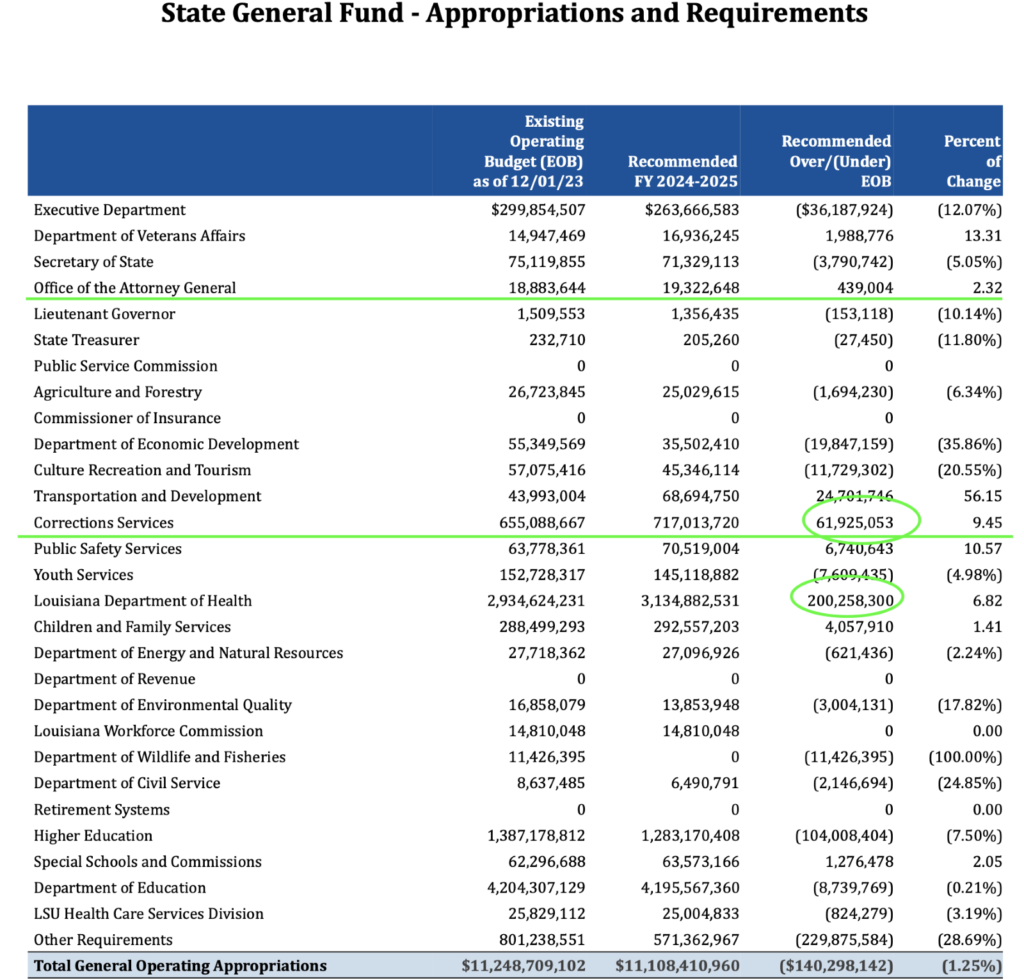

Despite the number of people incarcerated going down since the 2009 – 2012 peak, the cost of locking people up continues to climb past $1 billion dollars and beyond.

One look at the overall budget, and it is clear prisons are a massive part of the statewide budget and are at no risk of being cut.

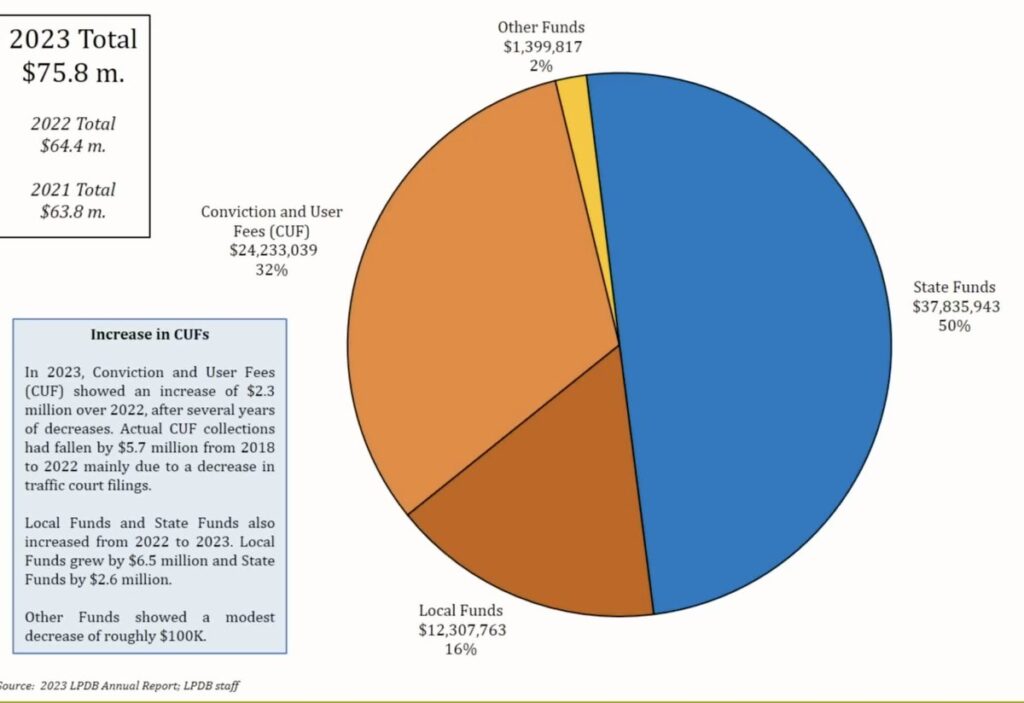

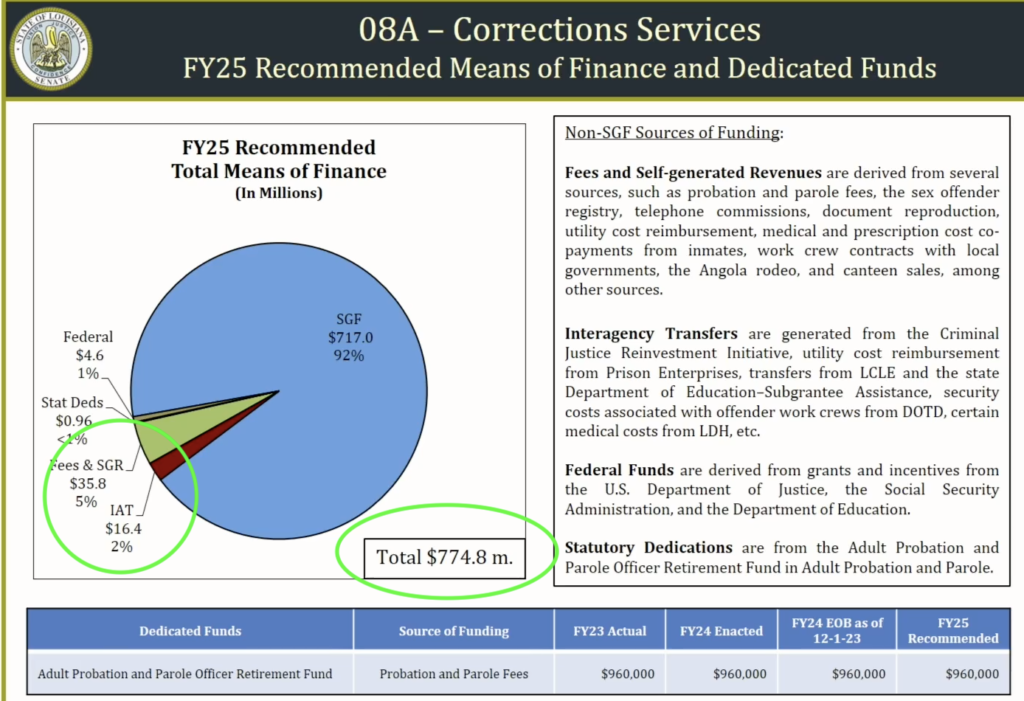

To cover up this major expense, politicians might seek to focus on “user fees,” such as probation fees, canteen profits, telephone kickbacks, or medical co-pays.

The users, however, are overwhelmingly penniless and it never adds up to any substantial percentage of the budget.

BUDGET DRIVERS: RETIREMENT AND MEDICAL COSTS

Why is incarceration so steep? The majority of funding goes to staffing expenses (more on that below), and to the thousands of retired staff who continue collecting a pension. Unfunded Accrued Liability (“UAL”) is not our expertise, but this is the amount of expected monies owed that do not have funds set aside. You can see that the Corrections budget has over $103 million (18%) going to UAL and retiree’s insurance.

Another major cost is medical care for patients in prison. According to the DOC, in their legislative presentation, total medical care spending is “somewhere around $100 million.” The monies are partly found in bills for people sent to the outside doctors, partly in the particular facility’s budget, and partly paid out to the local jails where people are detained.

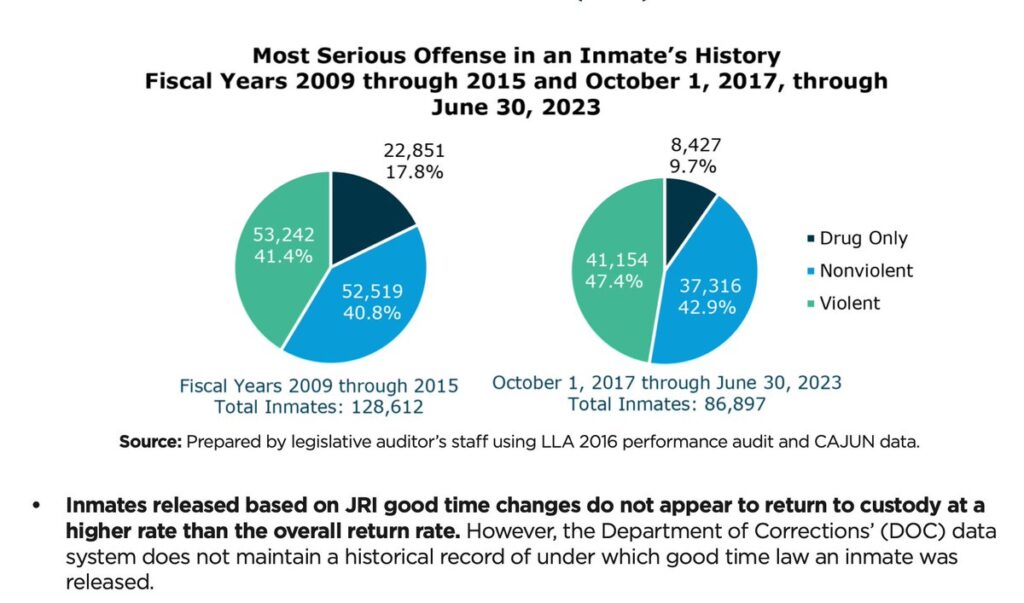

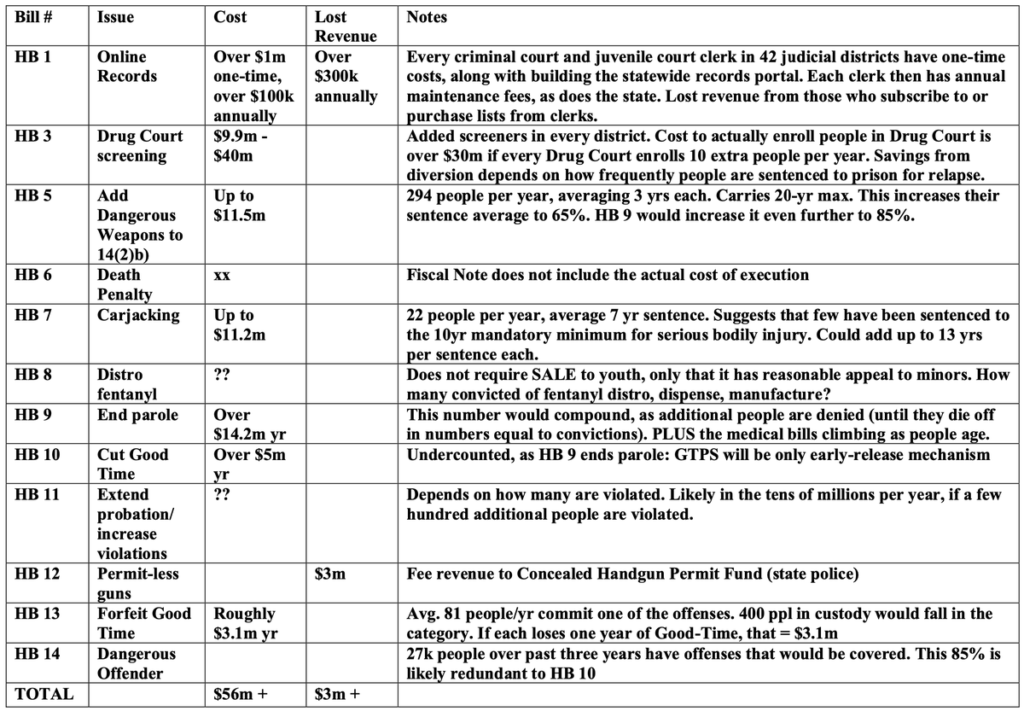

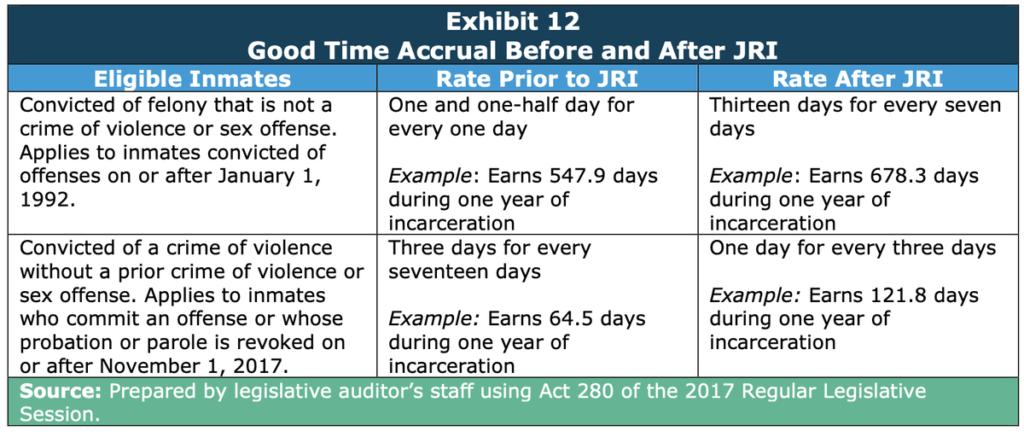

The Legislature’s 2024 Special Crime Session passed several new laws that should make the medical costs skyrocket as people get older. Eliminating parole (including medical and geriatric) and major cuts to Good Time credits will increase sentences. Narrowing parole for people already inside (unanimous parole decision) will turn other people’s sentences into Death Sentences.

The Lewis v. Cain case on Angola’s unconstitutional health care is forcing that institution under federal receivership. Costs will go up as care becomes legitimate. And lawsuits should begin against every facility that houses people, as none of them provide anything close to a reasonable standard of care.

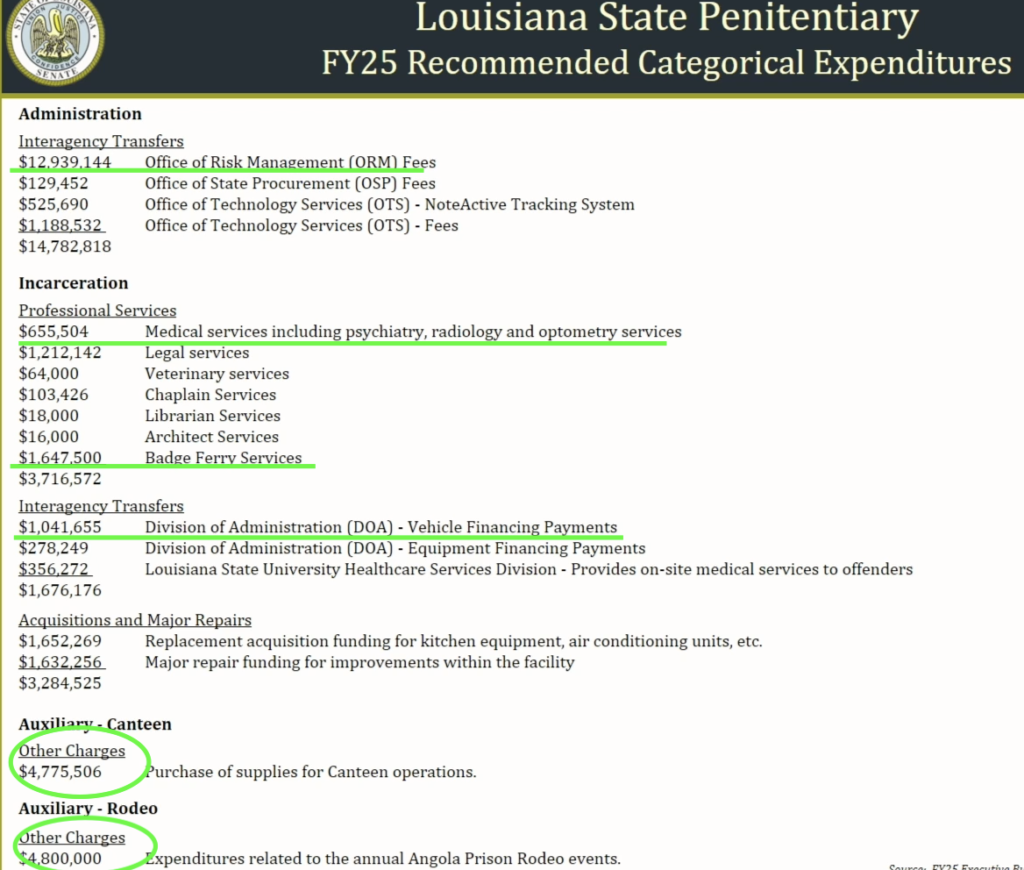

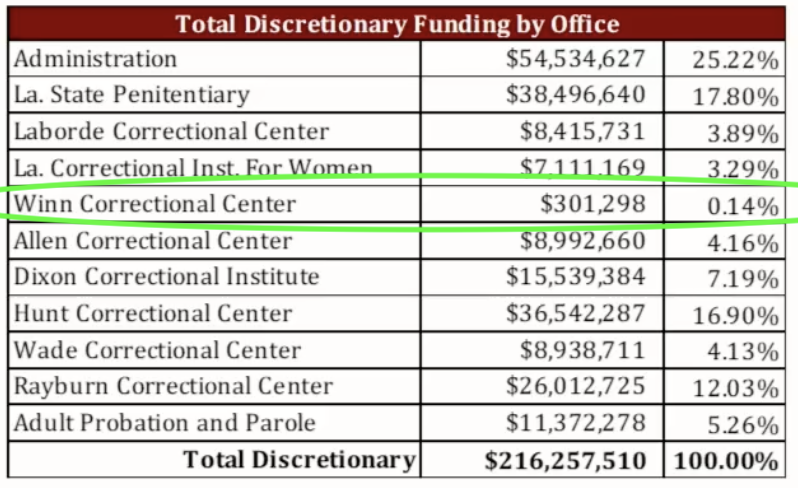

In the Corrections budgets, you will see them broken out by the overall statewide administration, and then each of the facilities in the system. The Louisiana State Penitentiary, AKA Angola, has the most incarcerated people who are the oldest and most likely to die in custody. Every facility budget has a few things that stand out:

- Office of Risk Management fees (Angola: $12.9m)

- Medical services ($1.1m)

- Vehicle financing payments ($1m)

Angola also has $1.6m going to Badge Ferry, which likely refers to the prison ferry that crosses the Mississippi River for employees. It is unclear if that ferry still operates, and it is well known most of the staff live at the penitentiary itself. Angola’s budget is also peculiar in having costs for putting on the infamous rodeo, but it is unclear where the profits from these weekends fit into the budget. Meanwhile, every facility will put in costs for purchasing canteen supplies; however, if this is referring to the items incarcerated people are buying with their own funds, we know the prison runs an overall profit on that exchange.

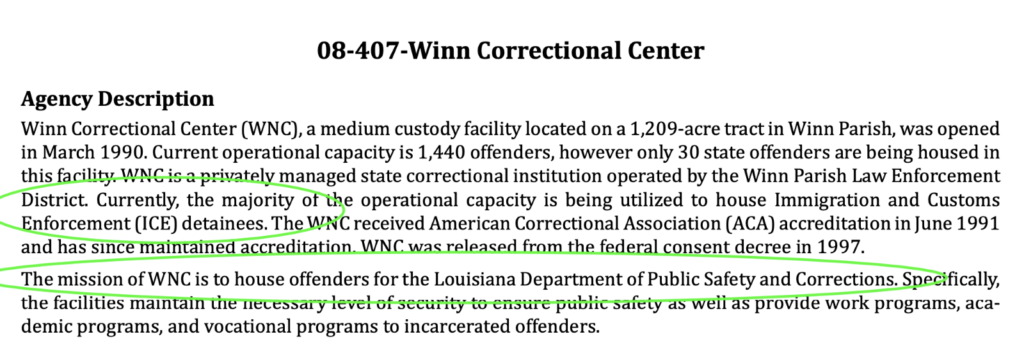

Looking at the overall summary, it is clear that another big piece is keeping the buildings functional, constitutionally compliant, and large enough to handle the influx of people. One shrinking part of the budget is in regard to Winn Correctional Center. In the Feb. 28 budget presentation at the Senate Finance Committee, it was noted that this prison is being leased out to the sheriff in Winn, “for about a million dollars.” It isn’t clear where that million is reflected. DOC Undersecretary Bickham explained to the House Appropriations Committee (March 6, 2024) that there is a Cooperative Endeavor Agreement in place, and the state can take control back from the Sheriff at any time, with roughly six months’ notice.

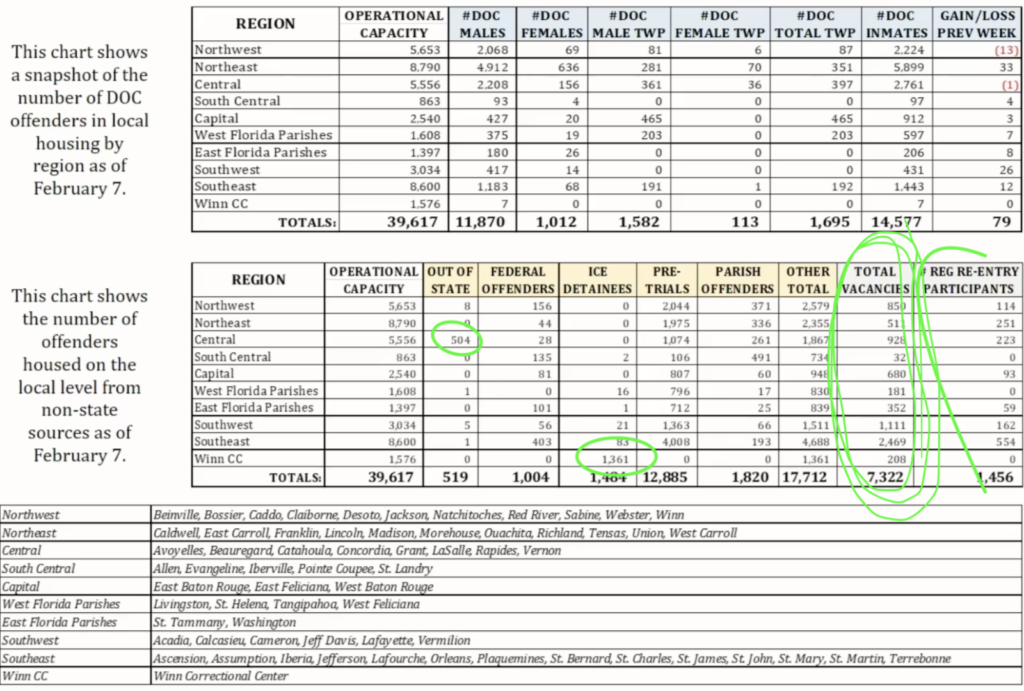

STATE BUDGET: SUBSIDIZING LOCAL JAILS, SHERIFFS, and DEPUTIES

According to the budget report, the mission of Winn Correctional Center is to ”house offenders for the Louisiana Department of Corrections.” However, it isn’t doing that. Instead, they are renting the beds out to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). During the Trump Administration’s massive border detention crackdown (which neither turned people back nor let them stay free pending their administrative hearing) Louisiana rented bed space to ICE for nearly 10,000 detainees. This is likely a large reason why the sheriffs had no qualms with the prison system contracting the way it did. The Feds pay a much higher rate per person. With that number coming down quite a bit, perhaps this contributes to why Gov. Landry deployed our National Guard to the Mexican border.

We are unsure why ICE or Winn Parish Sheriff, who uses LaSalle Corrections to administrate the prison, would want to obscure any details in a contract between two public entities, but it appears that somewhere around $65m is transferred between federal public funds to Winn, according to the Sheriff’s budget report. The entire parish population is only 13,755, and likely includes the number of incarcerated people. It is easy to see why a sheriff’s $14m payroll, pensions, plus local contracts contribute to political influence.

You may be wondering: Can the state lease out one of its facilities to a sheriff, who can then turn a profit with the federal government? And then pay for some incarcerated workers to help staff the facility?

It’s important to understand the relationship between state and local facilities. These parish jails were built in bulk during a time when the state subsidized construction costs and guaranteed the population to be detained. A great summary of this process is in “Prison Capital” (2023) by Lydia Pelot-Hobbes, who was a recent guest on the “From Chains to Change” podcast (listen here).

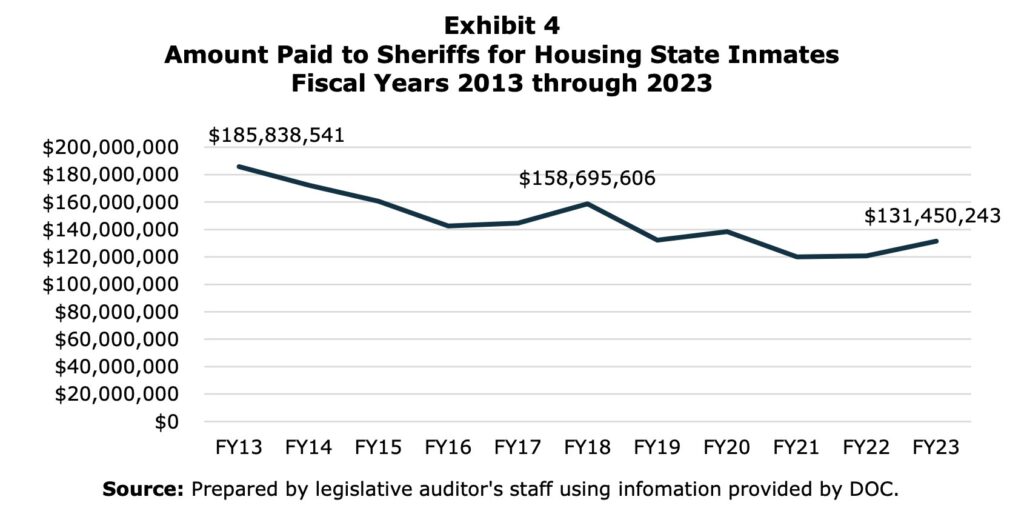

When the state facilities are bursting, the overflow goes to local jails run by sheriffs, with a per diem paid (less than half of what ICE pays the Winn Sheriff). Traditionally, the state/local balance was about 50/50, but taking Winn offline for state incarceration has led to the local jails holding more than the state prisons. While our prisons report only 781 total vacancies, and only 21 releases per day, the local housing has 7,322 vacancies. And naturally, the budget is confusing as to whether Winn is a state or local facility.

At times, this math does not add up. Rep. Kimberly Coates (D-73) of Tangiapahoa brought up a dilemma in her parish. The local jail is full of state prisoners, for which the sheriff collects the per diem from the state. Meanwhile, there is not enough room for locally arrested people. This forces the parish (not the Sheriff) to pay $800,000 to ship these people out to other jails.

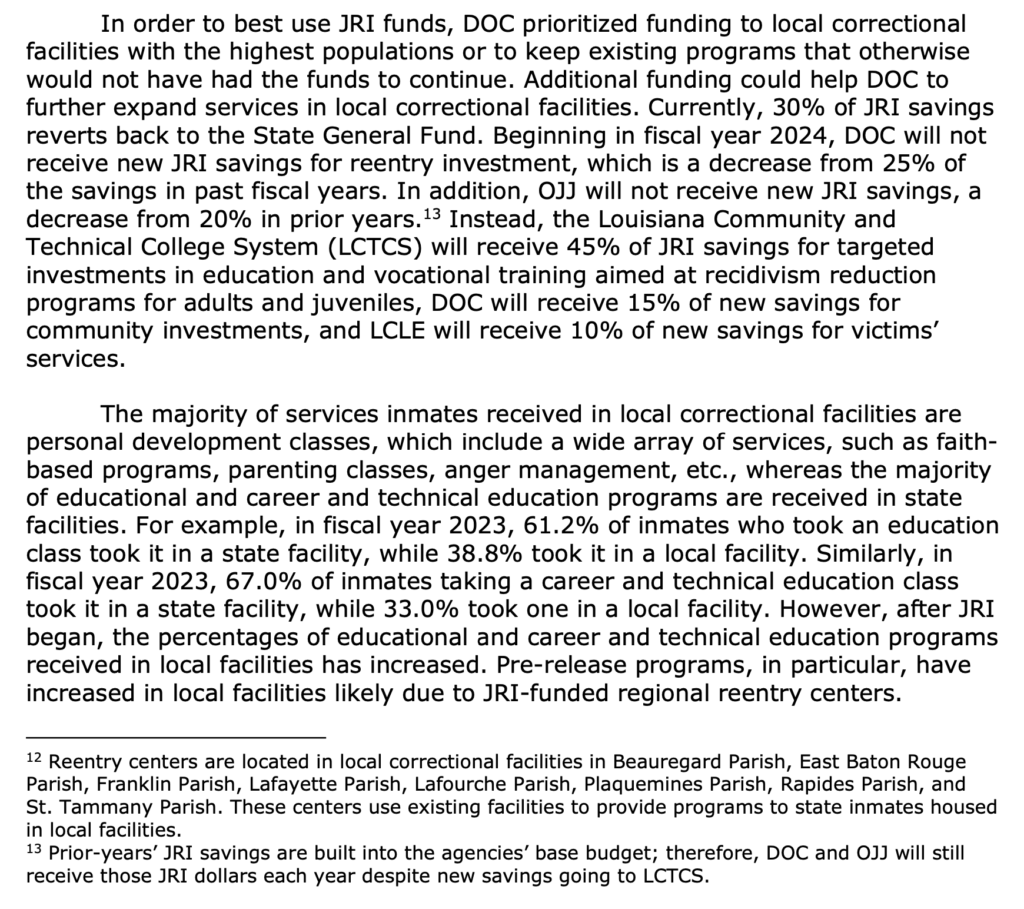

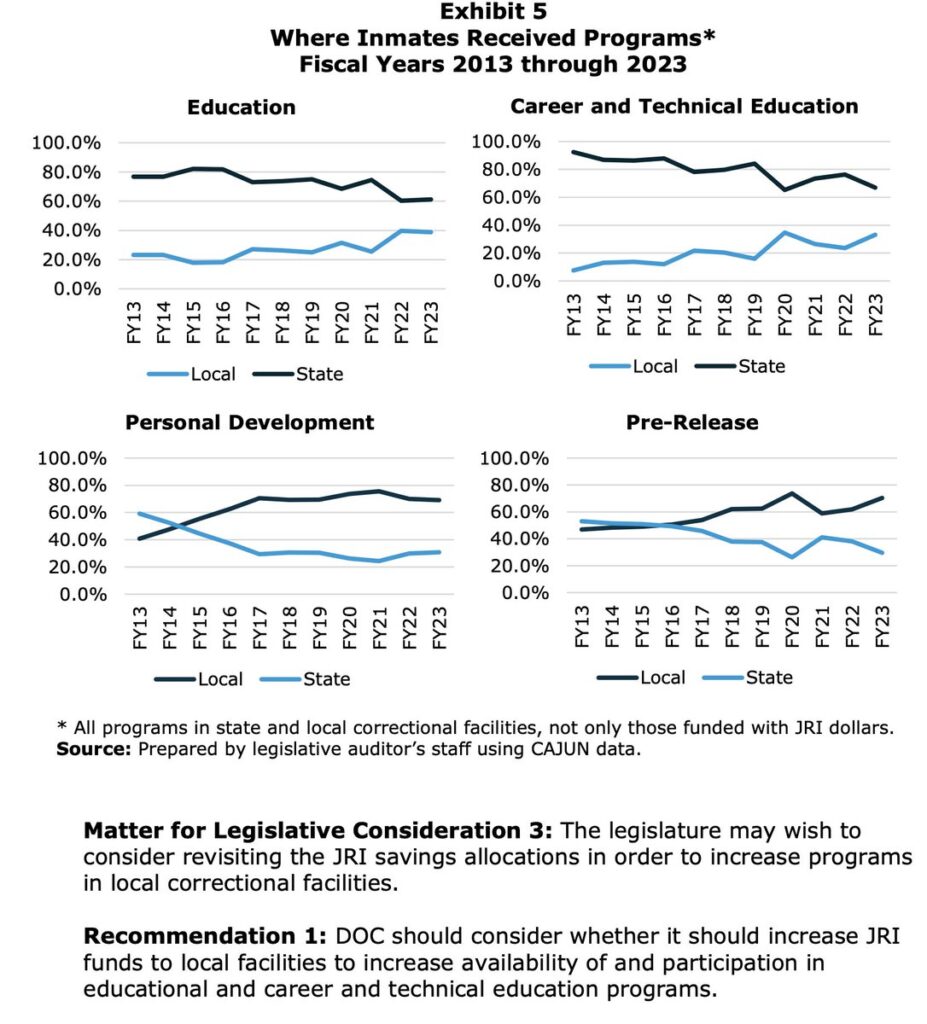

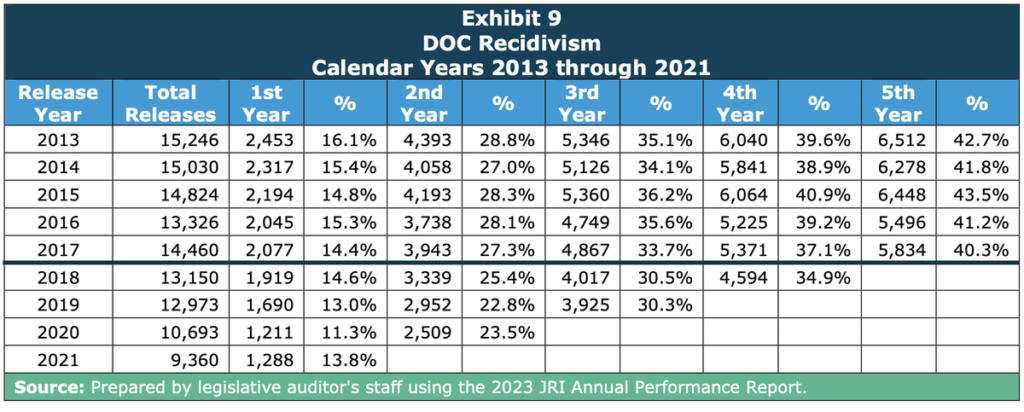

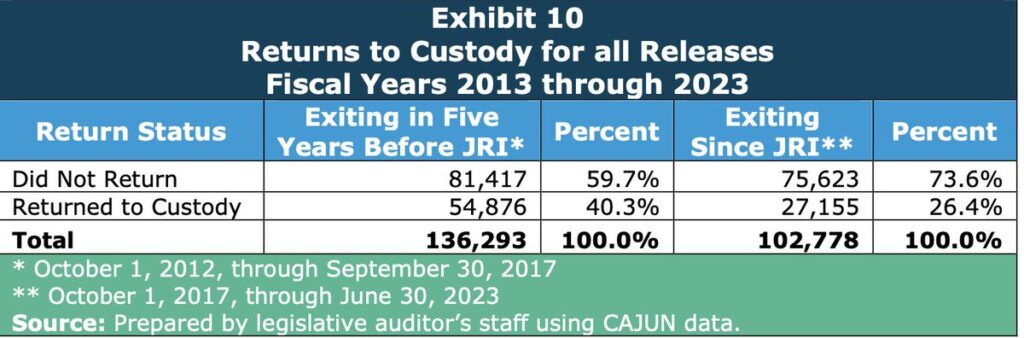

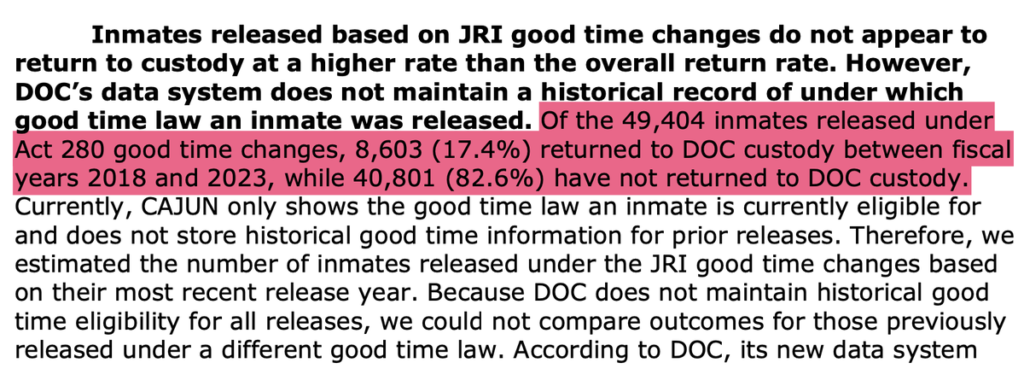

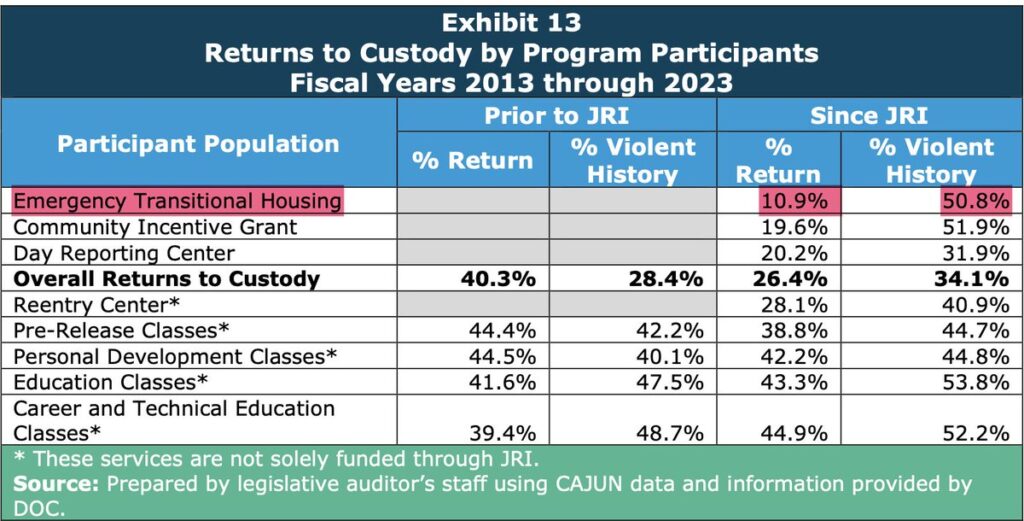

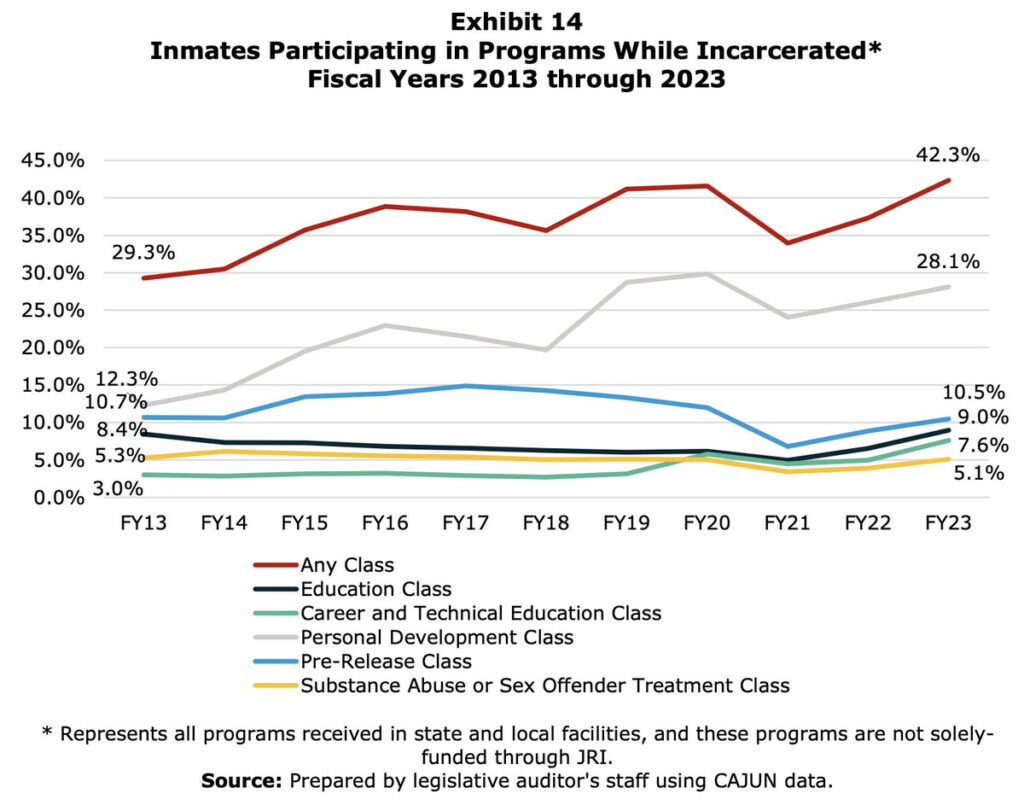

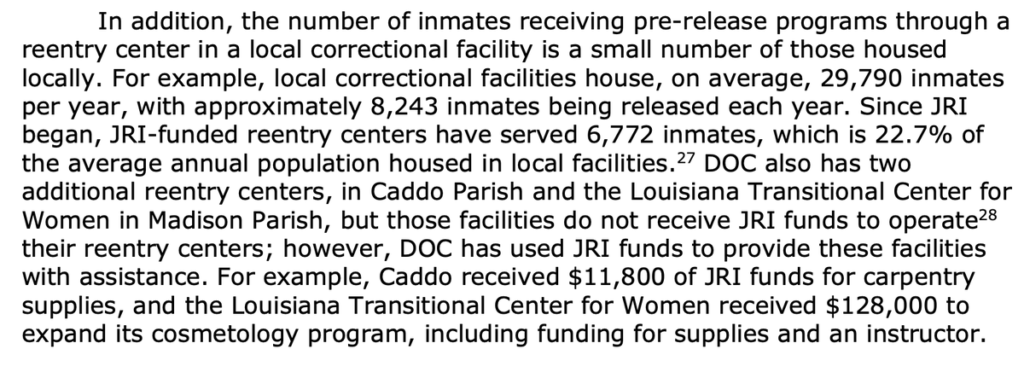

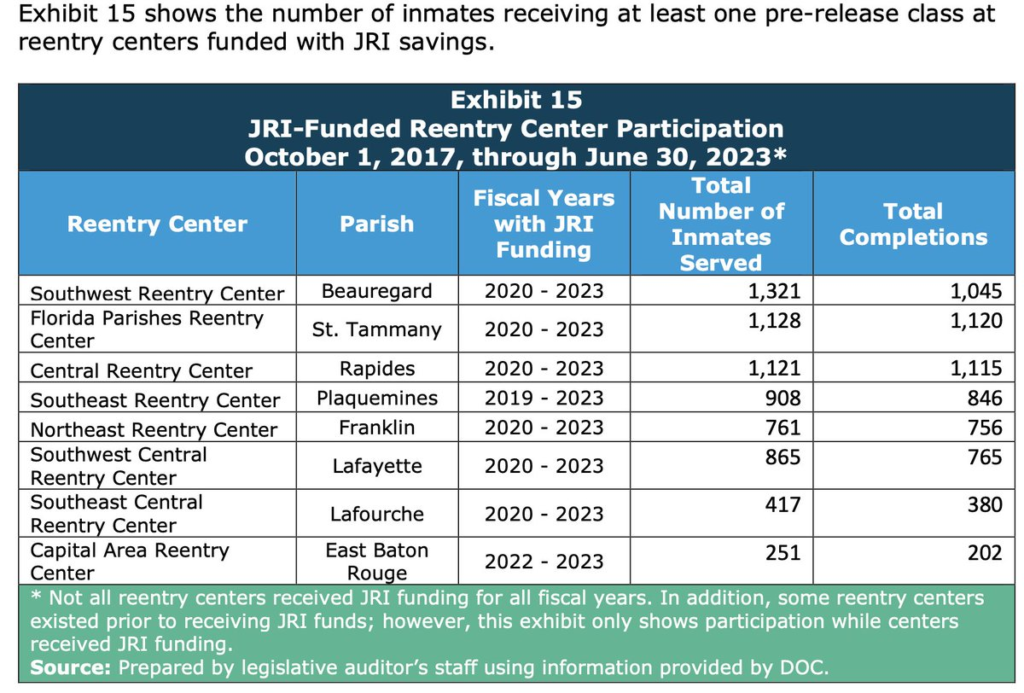

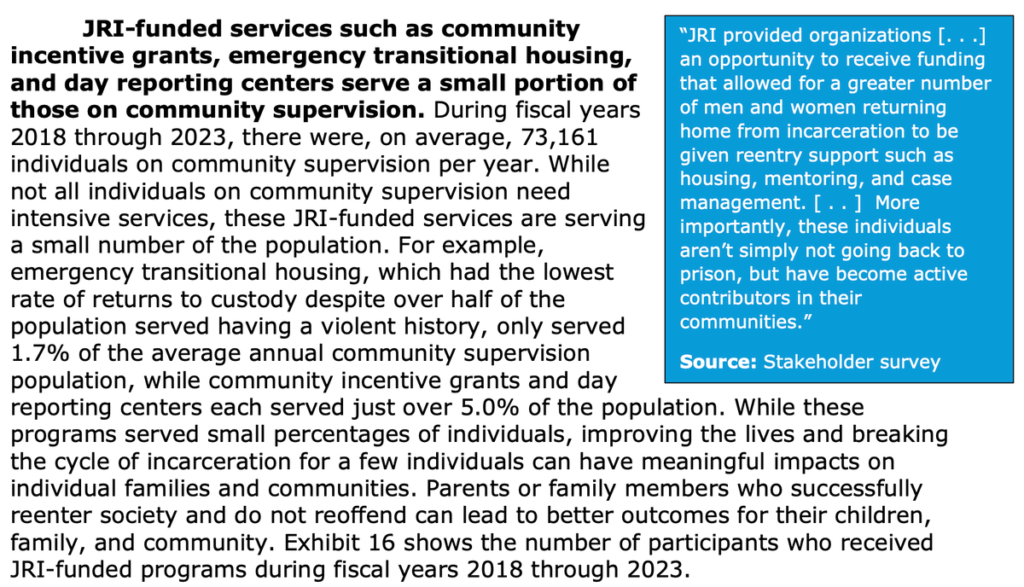

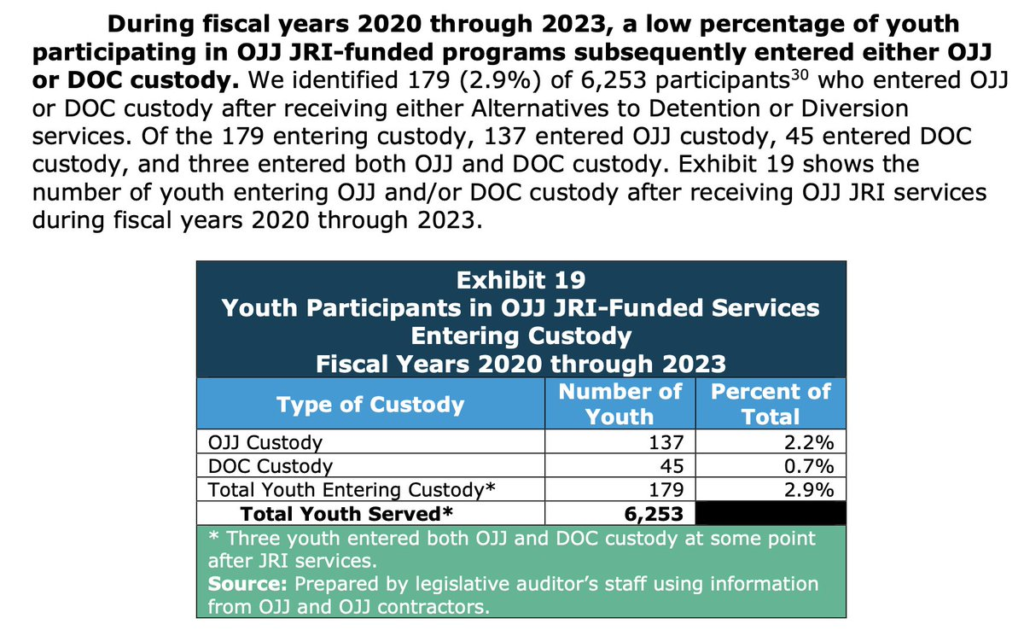

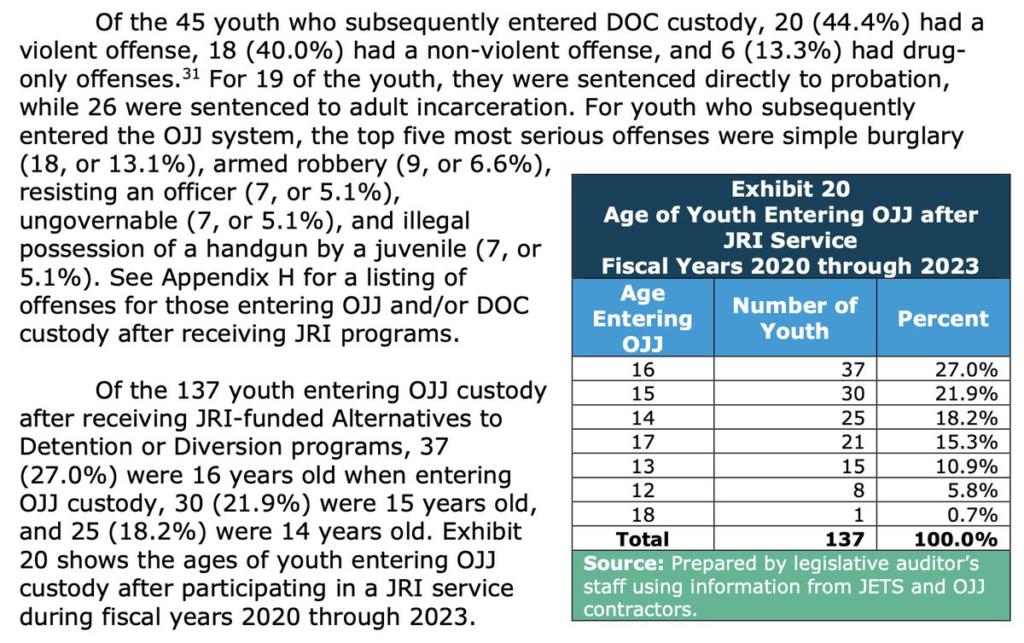

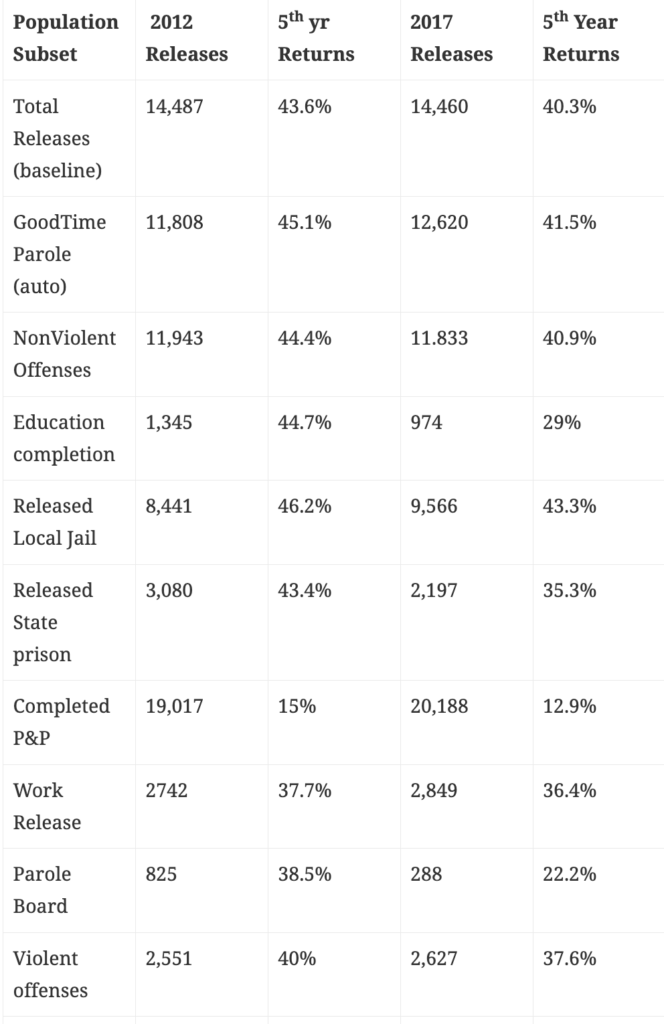

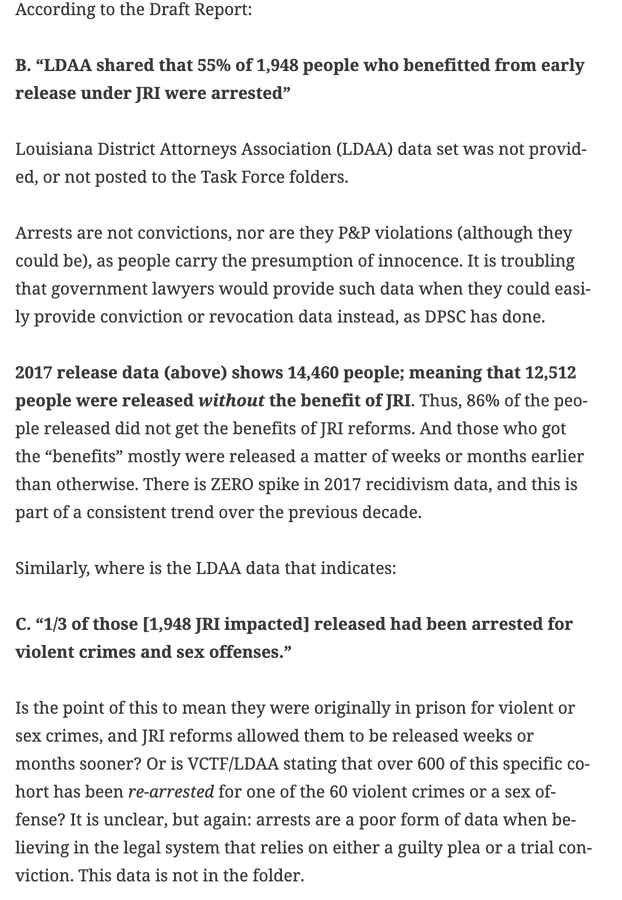

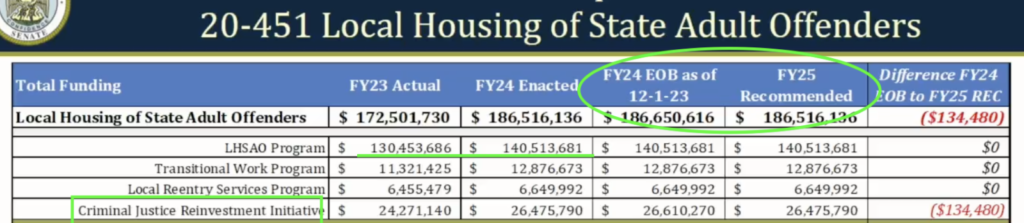

Also noteworthy in the above graphic are the 1,456 “Re-entry participants” at regional programs inside the local jails. This is a fraction of the 11,870 people serving state time, but part of the programming funded by the Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI). For those clamoring “JRI didn’t work,” we never once heard them criticize the sheriffs and their programming.

The state has an operational carceral capacity of 14,359 (not including Winn), and 13,505 people are housed. Local jails, on the other hand, can hold 39,617 people, and only 12,885 are being held pre-trial. It is clear who stands to gain by decreasing the use of bail, increasing probation and parole violations, and lengthening sentences. And we also are unlikely to see them give back the $26m in savings from JRI.

With the state prisons relatively stable in population, unless Winn’s lease is canceled, it is the local jails, run by sheriffs, whose funding was in jeopardy by increasing rehabilitation, decreasing recidivism, providing reentry support, scaling back discrimination, and downsizing prisons. The JRI funding to sheriffs was tailored to garner their support.

For details on Industry Employment (p.11), Costs Beyond The Jail (p.16), and more, read our full explainer: https://www.voiceoftheexperienced.org/s/2024_03-DOC-Budget-Explainer.pdf.