Who represents the civil rights of the people incarcerated in New Orleans’ jail? They don’t know. Do you?

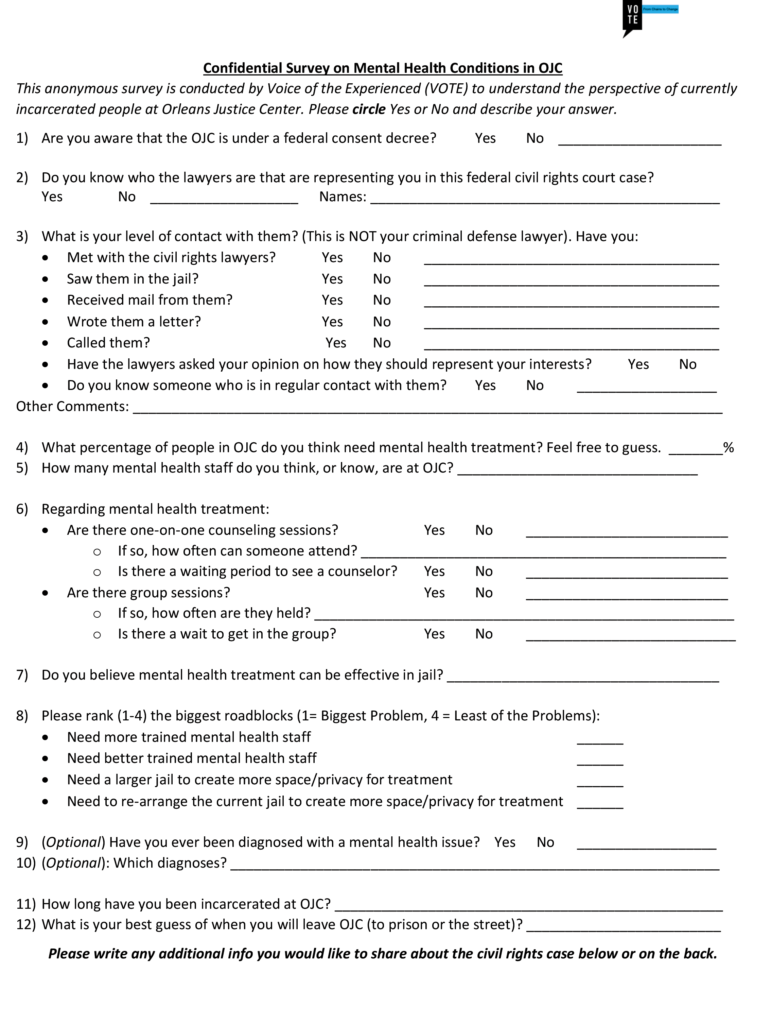

Voice of the Experienced surveyed people incarcerated at OJC about the consent decree and their experiences with mental health care in the jail.

“Who are these people? OJC is understaffed and run terribly. Why would you need another jail?”

– Community Member incarcerated 5 years at OJC, in response to our inquiry on the civil rights lawyers representing them

“No one residing at OJC has been informed of the civil rights case before 7/11/2023, when these surveys were issued. The mental health staff to resident ratio is way too large. The staff is not equipped to deal with the amount or level of mental health issues of residents. Medication services are sporadic and not on a reliable schedule.”

– Community Member incarcerated 16 months at OJC, diagnosed with anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Expecting to leave OJC “within a year or two.”

AUGUST 1, 2023—In the ongoing saga of the proposed $110 million dollar Orleans Justice Center (OJC) expansion, a critical question remains unanswered: who truly represents the people incarcerated in our jail?

We, Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), raise strong concerns about the representation of the community most impacted – the people currently incarcerated and who could be incarcerated at OJC – by the MacArthur Justice Center (MacArthur). The 2012 federal court Consent Decree was intended to bring meaningful change to the abhorrent jail conditions in New Orleans and meet standards mandated by the United States and Louisiana constitutions. But instead, it has devolved into a labyrinth of murky intentions and questionable judgment that we believe would make mental healthcare at the jail worse.

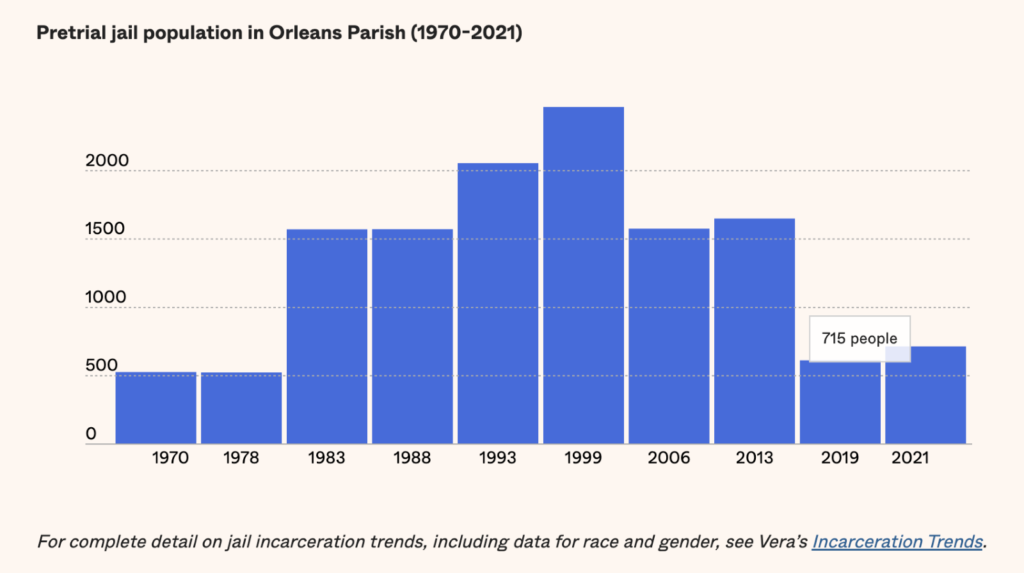

More than a decade into the litigation, at least 100,000 people have been in that jail, held for periods ranging from a few days, to a few weeks, to a few months. We are totally surprised that MacArthur supports a $110 million panopticon jail expansion to house a few dozen people with serious mental illnesses (SMI). It is understandable for others to put weight in their opinions, as MacArthur is tasked with representing the incarcerated people inside the jail. We have heard Judge Africk, Magistrate North, and City Council give credence to what the jail’s incarcerated people want (which is rarely the case for people in jails and prisons). We hope such deference continues after reading this letter.

Our concerns have reached the point that we feel the necessity to raise them in a public forum. The fate of our jail and its population should not be directed through private court deliberations limited to pleadings by a few lawyers, but in public dialogue. This is for the people of New Orleans.

A Brief History of the Orleans Parish Prison / Orleans Justice Center Consent Decree

“I’m unsure of what that means.”

– Community Member at OJC, when asked about the “Consent Decree.”

The Consent Decree is an agreement, overseen by a federal judge, of a 2012 class-action lawsuit brought forth by a group of 10 incarcerated whistleblower plaintiffs in Orleans Parish who had the courage to speak out on the dangerous conditions and lack of mental healthcare treatment in the jail. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) originally represented these individuals. Within a year and a half, when the original lead attorney switched organizations, MacArthur replaced SPLC’s representation of them.

At the time this litigation was initiated, the jail regularly detained roughly 3,600 people. Conditions in the jail were so egregious that the federal government moved to join the plaintiffs to sue Sheriff Gusman, following an independent investigation conducted by the Department of Justice. By the end of the year, these three parties entered into a federal court Consent Decree, agreeing to work together to make the jail conditions in New Orleans constitutionally compliant (which is still a very low standard of existence).

Importantly, the Consent Decree acknowledges that the “Plaintiff” class now represented by MacArthur consists of “all individuals who are now or will be imprisoned” in the Orleans Parish Jail. This court document starkly contrasts with MacArthur’s regular claim that they solely represent the individuals currently in the jail.

In addition, the Consent Decree outlines a series of steps that the Sheriff must take in order to improve the conditions at the jail. These improvements require funding, which prompted Sheriff Gusman to sue the City of New Orleans to pay for them. Over the last decade, the City and Sheriff have come to several agreements on how to fund the Consent Decree, which have required the City to foot much of the bill. City Council oversees the checkbook to fund the changes in the jail but is not a party to the litigation.

The taxpayers have funded all sides of this litigation. VOTE and its members absolutely support improving the conditions at the jail and understand that funding is required to make the necessary changes. However, considering that both the class of Plaintiffs includes us (people who could be incarcerated in the jail), and that taxpayers are funding the Consent Decree, we are concerned that the process of making decisions that impact us is not democratic.

Members of the free community in New Orleans, including Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), have worked tirelessly for decades to bring these issues concerning the jail’s abysmal conditions into public dialogue. Our work began long before this litigation and has continued since the Consent Decree was first agreed upon. We have regularly organized throughout the implementation of the Consent Decree to ensure those most impacted by the jail have a voice at the table.

Since the start of this litigation, voters have chosen a new sheriff, new mayor, and new City Council members. The original SPLC attorney is gone, and even a Compliance Director (who took over the jail from Sheriff Gusman) came and went. Yet, We the People remain.

The People Stop Sheriff Gusman from Trying to Expand the Jail – Twice

In 2010, Sheriff Gusman originally wanted to use FEMA funds for a massive 6,300-bed jail, which would double the jail’s previous capacity and have crippling operating costs. In response, we organized, and the City Council passed an ordinance creating a max capacity of 1,438 beds. In 2015, Gusman opened a $145 million jail which was flawed from the start. In 2018, after VOTE sued Sheriff Gusman for using the Temporary Detention Center (TDC), which was meant to be demolished, the City Council ultimately granted permission to use the building. However, this arrangement came with a further reduction of the bed cap to 1,250. The TDC is where people with SMI have most recently been housed at the jail.

“Another thing is the condition of this facility, OJC. It is only 7 years old, yet half of everything is broken.”

– Community Member detained nearly 6 months, aware of the Consent Decree, but mistakenly names a criminal defense lawyer as the federal civil rights lawyer.

Phase III Has Virtually Zero Public or Political Support

Federal law dictates that a federal court cannot order New Orleans to expand the jail in order to provide constitutional care for people being detained. Judges are also limited in the specific orders they issue. For example, when a federal court in Baton Rouge ordered the Louisiana Dept. Of Corrections to install air conditioning on Death Row, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision, ruling that the court can order the temperature to come down (the result) but not the specific means to get there.

Instead of explicitly ordering jail construction, the federal court is ordering the current sheriff and current mayor (who oppose the construction) to uphold an agreement between the past sheriff and past mayor to build “Phase III” … which also requires the City to cut tens of millions from other programs for this unneeded jail expansion, while also setting aside millions per year for maintenance. And for what – 56 glass cages of a medieval design that has been deemed “inhumane” and “ineffective” by experts? Whatever deal Gusman and Landrieu may or may not have made to build Phase III is long gone now.

The people have spoken on the jail expansion via the past Sheriff election, a series of zoning hearings, FEMA’s public feedback, and at the latest City Council hearing. We can’t recall a SINGLE sign of public support to build this proposed jail expansion. We have also never heard MacArthur testify in support.

This past April, when voters could decide to increase the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office funding by a fraction of the proposed jail expansion, to fix the initial jail construction, only 9% of voters approved the proposal. Without the people hearing directly from MacArthur, it is anyone’s guess as to why the organization supports a construction project that would strip down the city budget in exchange for a cruel and unusual circle of glass cells that would surely be the subject of litigation itself.

VOTE is Committed to True Change at OJC and Across Louisiana

If anyone wants improved healthcare and conditions at OJC, it’s us. But not like this.

We at VOTE have a vested interest in the jail – it’s in our organizational DNA. VOTE was birthed inside of the Louisiana State Penitentiary as the Angola Special Civics Project and became an official grassroots nonprofit once our founding members were freed. For the past two decades, we have been at the forefront, advancing civil and human rights for those impacted by the criminal legal system. We have been party to federal and state litigation, written legislation, and are known for our work to end non-unanimous juries. We work to remove the barriers that people with convictions face in accessing the ballot, housing, employment, health care, jury duty, and more. Our monthly meetings in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Lafayette regularly draw hundreds of dedicated members. Many of these members are currently on probation or parole. We also have VOTE members on the inside and regularly communicate with the currently incarcerated community prior to doing anything on their behalf – it’s a tenet that underlies all our work. #nothingaboutuswithoutus

Roughly half the people going into the Orleans jail are on probation or parole supervision. Those of us on probation and parole are already on thin ice, and often struggling with a job, housing, and transportation, while dealing with trauma, poverty, backloads of bills, and much more. When we are accused of a crime, have an old traffic warrant, or even just stopped for looking suspicious, we are typically held without bail for an extended period to work out these logistical delays and mountains of administrative paperwork that must be climbed. Thus, everyone on probation and parole in New Orleans has a heightened interest in the conditions of the jail. Considering that so many of our employees, members and supporters are at risk of being incarcerated at the parish jail, we at VOTE are especially concerned with the enforcement of the Consent Decree.

Questionable Representation of Current and Future Incarcerated Communities

MacArthur lawyers tell the media that their clients want a jail expansion. They imply that they are speaking on behalf of those with serious mental illness currently being held in the jail. However, considering the proposed glass cages of this jail expansion would not be available for three years, their “clients” in question are most likely not currently in the jail. Instead, those that the new jail would impact are future clients. MacArthur claims to also be speaking on behalf of this community.

Whether MacArthur sees their representation confined to a specific group of current or future clients, we found it difficult (based on our collective experience) to believe anyone would be in support of a glass panopticon being built over the next three years – so we went to the source – the residents currently incarcerated at Orleans Justice Center.

On July 11, three VOTE organizers, all formerly incarcerated men, went into the jail to pass out anonymous surveys on mental health and the Consent Decree. All three had been previously cleared to serve as volunteers in the jail to help create mentorship programming. We made the survey anonymous to ensure we protect the people whose lives are not under their own control. Our survey was imperfect, particularly considering there are people in OJC who have challenges with reading. A handful of respondents clearly conflated their own defense attorneys (even naming several public defenders), which makes sense when people had no idea about the Consent Decree or MacArthur.

One person, incarcerated 6 years, noted that “the employees informed me,” of the Consent Decree and referring to the lawyers: “I would like to meet them.” Another person, inside for 11 months: “Why don’t I know about this[?]”

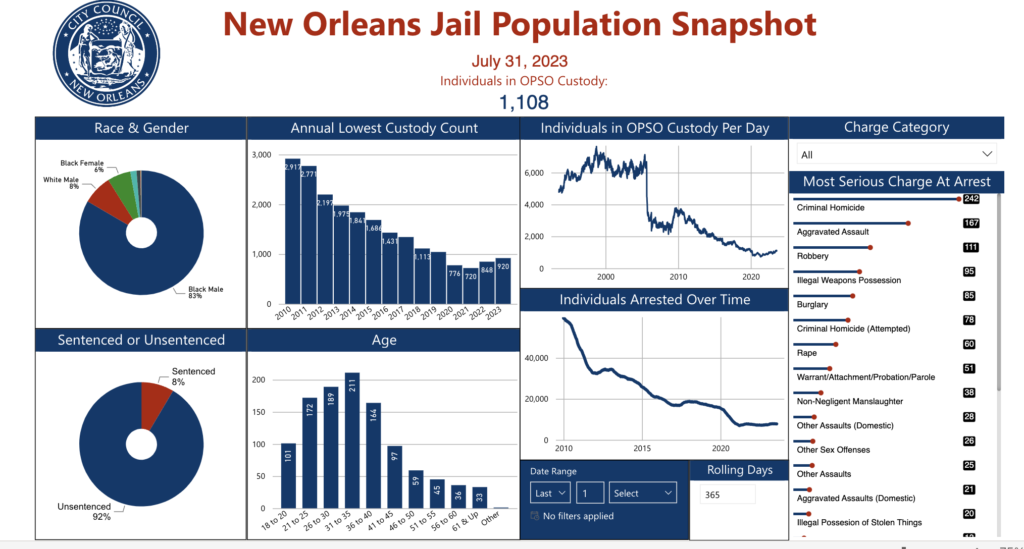

Ultimately, 211 incarcerated people filled out a survey. They represent 19% of OJC’s current occupancy of 1100 people. Of those that completed the survey, 75% had no idea the jail was under a Consent Decree, 95% were unaware of who their lawyers were and only two could name MacArthur Justice Center as their representation – one who was incarcerated at OJC for almost 5 years and the other for 2.5 years.

Two people stated they have been incarcerated at OJC for over 10 years. Both were diagnosed with mental health issues; neither knew about the Consent Decree.

Of the 100,000 people going through the jail doors, how many were provided with information about the case? Does anyone receive the right to opt out of the class? To hire a new lawyer? More to the point, how does a lawyer follow the Rules of Professional Conduct when they have 1000 clients who turn over every few months? If they took the time to meet with all of them, it is peculiar that 99% would not recall the meeting. And as for those with SMI, how does a lawyer ethically represent the strategic decisions of someone who may not be competent to stand trial?

Lawyers have a duty to keep clients informed so they can intelligently participate in strategic decisions. With only 1 of 211 surveyed responding that they had spoken with a MacArthur attorney (Emily Washington) about this Consent Decree, does this one incarcerated person (incarcerated over 2 years, and expects to leave OJC in a year) speak for the other 1099 people in the jail?

“I have requested to speak to a civil rights attorney and was told my family would have to contact the ACLU for me.”

– Community Member incarcerated 5 months, who had not heard of the Consent Decree. Expecting to leave OJC this month.

As for those of us who could be sent into the glass panopticon in the back part of this decade, who speaks for us? Are we all clients now, at this moment (as potential detainees), or do we only become clients upon arrival in the jail? Do ‘We the People’ have no say in our jail conditions until we end up in there? Do we get an attorney-client agreement upon arrival?

“I would like OJC to be more serious about mental health. I’ve been in here suffering with deep flashbacks on my sexual assault that happen to me. All they do is give me papers to read and small talks that never help because they are never on topic. They don’t give me the meds that I am supposed to receive. It’s like they don’t care. Nights I can’t sleep. Days I feel hopeless.”

– Community member at OJC for 3 months, never heard of the consent decree, diagnosed with anxiety, bipolar, depression, ADHD. Expecting to be released this month.

Mental Health Care is a Public Health Issue that Needs Public Health Solutions

“I believe that the entire staff here needs to be addressed. And that every inmate has a problem with something. Addiction, mental, or we wouldn’t commit crimes. We need help.”

– Community member incarcerated at OJC 6 months, expecting to leave OJC “soon,” and was aware of neither the consent decree nor of MacArthur.

New Orleans needs a deep conversation about mental health treatment for its residents both inside and outside the jail, and it would be ideal to discuss causes (such as disaster trauma, poverty, lack of health care, hopelessness, and toxic environment) as well as committing anything close to $110 million in solutions. Many of our residents could avoid jail-based mental health needs if New Orleans had systems that address needs for (1) children, (2) the unhoused, and (3) provide robust alternatives when judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers all agree someone needs help, not handcuffs. People are self-medicating in lieu of proper treatment. We also need to be realistic about what mental health treatment looks like for people in jail for a night, a week, a month or longer. We need to discuss treatment beyond medication and “suicide watch.” Anyone who has ever been in therapy understands many of the challenges even under the best circumstances, and this includes trusting one’s therapist and feeling safe in a group. This is nearly impossible in a jail setting, where a person is best advised not to share any personal information with others. Glass cages won’t fix that. And as was said at the City Council hearing last week, people who suffer from various ailments will face the crippling anxiety of being fully exposed.

Of the two detained people who could name MacArthur as their civil rights lawyers, one was not sure if they were ever diagnosed with a mental health issue.

“I have tried to have a diagnosis for several years, although I am prescribed many psychotropic medications. Seroquel 400mg Triliptol 600mg Zoloft 100mg. The facility refuses to give me a diagnostic exam.”

– Incarcerated almost 5 years, expecting to leave OJC “within the next few months.” This person notes they have never met with the civil rights lawyers, and MacArthur never asked their opinion on representation.

The recent jail monitors’ report revealed that the current mental health provider fabricated wellness checks for people on suicide watch and had unqualified people making diagnoses and course of treatment plans for people with mental illness. Imagine spending $110 million on a new building, and then trying to staff it, when staffing challenges have plagued the jail for many years and the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office annual budget would need to balloon even more to keep this added facility open.

There is no outdoor recreation in the New Orleans jail, and there could be a yard where they want to expand the jail. Jail life is so dystopian, the architects, jailers, and even detained people refer to an indoor room, with a caged window (too high to see out of) as “outside” recreation. There is no chow hall. No exercise machines. Not enough phones, and even a snack costs far more in jail than on Broad Street. Fresh air and sunlight can do wonders for mental health. Yet someone has the idea that glass cages, with added room for “treatment,” will settle the mental health challenges. Yet people in our survey overwhelmingly said the primary problem is not room, it is better and more trained staff. Jail expansion for mental health was far and away the least of their issues. We wanted to know, so we asked directly, and received unprompted comments on mental health treatment such as “everything is just for a show.”

A public health approach to public safety would create a single provider for patients who may transition in and out of jail before finding sustainable freedom. Community health workers, such as those at the FIT Clinic (and proposed in Congress as The People’s Response Act) could assist the continuum of care people need when transitioning their entire lives into, or out of, jail. On the other end of the spectrum are people accused of the most serious crimes, whose competency to stand trial may be the goal for everyone except the patient themselves. We need to be honest if the end goal is to ship someone off to Angola (sane enough for “guilt”) or, in lieu of that, Eastern LA Mental Health System’s forensic division.

“If you don’t want to kill yourself or kill someone they don’t want to talk.”

– Community Member, incarcerated 6 years, in reference to counseling sessions at OJC. They are aware of the Consent Decree but have had zero contact with any lawyers in the case.

A Loss of Faith in MacArthur Justice Center

The law isn’t clear about the accountability of lawyers who represent a class of people, particularly one that churns over the course of 100,000 people in a decade. From whom do they get their marching orders? Who would be in a position to alter a strategic decision? And if those clients are locked up, without access to civic engagement, how are their voices heard? MacArthur has disappointingly rebuffed our attempts to meet with both local counsel and their national director. They have said clearly that they do not represent VOTE nor any other people in the city except those in the jail, as though this is a private matter. We have lost entire faith in their representation, especially if they take issue with our conducting a survey they should be doing on a regular basis. On their website, MacArthur has provided no case updates in five years.

In 2021, when the world learned through Netflix that Sheriff Gusman had filmed a TV show in the jail by exploiting women in pretrial detention, we were shocked to learn that MacArthur had previously taken this issue to Judge Africk, yet never brought it to the public.

Anyone can put on a website that they “represent people abused by our oppressive criminal legal system and fight to vindicate their rights, hold people with power accountable and reshape the law going forward.” However, to claim credible representation it needs to be backed up by actual people they represent. This applies in both the Rules of Professional Conduct and the court of public opinion.

We encourage people to reach out to the currently and formerly incarcerated to have a conversation about mental health and incarceration, to better understand potential improvements, and recognize what makes matters worse. Don’t take a lawyer’s word for it, find out for yourselves. This jail belongs to all of us.

“Jail is for accused waiting to seek justice. Mental health is for hospitals.”

– Community Member incarcerated 7 months, never contacted regarding the Consent Decree, expected release from OJC (to prison or the free world) within 10 days.

About Voice of the Experienced (VOTE)

VOTE is a grassroots organization founded and run by formerly incarcerated people (FIP), our families and our allies. We build power through community organizing, policy advocacy, and civic engagement. We are dedicated to restoring the full human and civil rights of those most impacted by the criminal (in)justice system. Together we have the experience, expertise and power to improve public safety in Louisiana and beyond without relying on mass incarceration.

Learn more at www.voiceoftheexperienced.org