Drawing up the documents to forge American democracy was an often fraught process—the many disagreements of the framers can be found in the Federalist Papers of John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton, and the personal writings of people such as Tom Paine, Ben Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson. Despite those disagreements, and the amended Bill of Rights that came soon thereafter, several key principles were without controversy; one of which is the “Separation of Powers” that creates our three branches of government who are designed to provide “checks and balances” on each other.

The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.

—James Madison, The Federalist Papers

The Legislative Branch, being the representative voice of the people, would create the laws. The Executive Branch, headed by an elected Chief Executive, faithfully carries out the will of the people. The Judicial Branch makes the wise rulings, including whether the Executive oversteps their authority, or if the legislature creates unconstitutional laws.

In Louisiana, the Executive Branch is represented by a term-limited Governor, along with district attorneys and sheriffs who are not term-limited. The DAs have a legislative lobby called the Louisiana District Attorneys Association (LDAA), and the sheriffs have a legislative lobby as well. These two groups are currently represented by Loren Lampert and Mike Renatza, respectively. These lobbying groups are the most powerful political forces in Louisiana. They write laws and amendments to other proposed laws. Nothing is passed over their objections.

The term-limited legislators consistently explain that they will follow the lead of their local district attorney and local sheriff, rather than follow the lead of their constituents. When a bill was proposed to term-limit sheriffs, the only testimony against the proposal were sheriffs themselves, not voters. The defense of no-limits was that voters could simply choose to unelect a 20-year incumbent, as though mounting a victorious campaign is so simple, particularly against a figure universally accepted as the most powerful political official in a parish, with the power to raise their own monies and who are not accountable to any oversight.

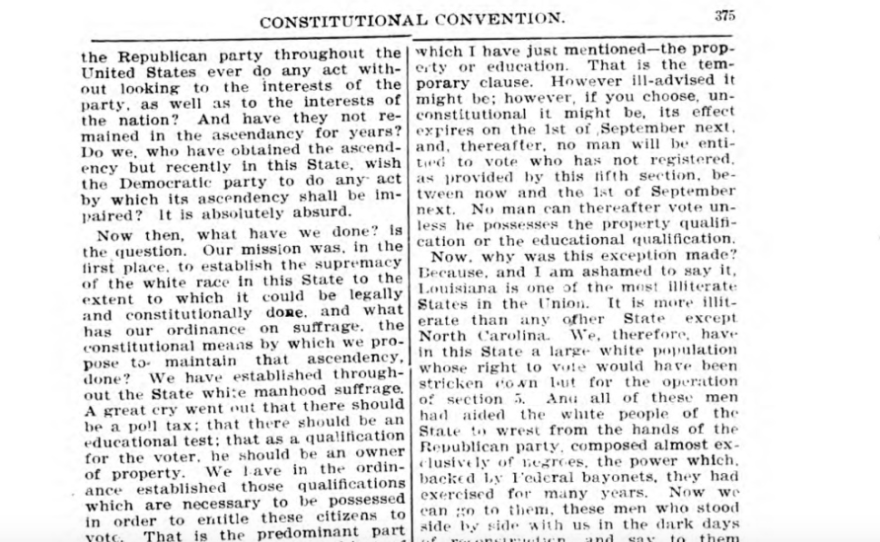

The U.S. Supreme Court was needed to declare Louisiana’s non-unanimous juries unconstitutional. After well over a century of district attorneys using this Jim Crow tool, which was explicitly created to ensure White Supremacy (a fact spelled out in the all-white Constitutional Convention of 1898, and universally accepted today), the LDAA fought the demise of 10-2 verdicts every step of the way. They fight it still. They, along with the Attorney General, will argue to the Louisiana Supreme Court that this unconstitutional tool (used only by two overtly discriminating states) should keep the fruits of their unjust labor. They will argue that every person still alive who was victimized by this tool should stay convicted. Case closed.

Last year, the legislature convened a task force to determine how to address the fruit of the poisonous tree, aka Jim Crow verdicts. The task force met only once, and legislators instead proceeded to draft a bill under the direction of the LDAA. Thus, rather than faithfully execute the laws as given to them by the people, they are crafting the laws. District attorneys also routinely endorse candidates in elections, as do sheriffs, thus using their influence to determine who sits in the seats.

The bill they drafted to address the problem of over 1500 people sitting in prison, despite one or two jurors holding out to the end with a “Not Guilty” position, would allow not for the reversal of a conviction; but instead create the possibility that a person might continue their conviction and sentence on parole. Most of these people were sentenced to Life (aka to die in prison) or a term so long it is considered “virtual life.”

The bill puts the LDAA in position to have full veto power over every applicant. Under the proposed scheme, the LDAA nominates three former district attorneys of their choosing, one of whom the Governor must choose to serve on a 5-person panel. Although the first iteration of the bill required 4 out of 5 votes to parole someone on an unconstitutional conviction, the LDAA won an amendment (over the objection of the bill sponsor himself) to make the vote unanimous. The sponsor, Rep. Gaines, a career police officer, called it “ironic.”

Using their legislative power to create a law that would review their own executive decisions, the LDAA places themselves in the role of the judiciary, to determine if there was a “miscarriage of justice.” And with that, the unification of powers is fully complete. The bill purports to say that panelists will recuse themselves where there is a conflict in the case (presumably referring to whether someone prosecuted a specific petitioner’s case) however, they are all conflicted on all the cases. First, the LDAA acts in unison, and the bill would even allow other district attorneys to submit their objections to the parole of any unconstitutionally convicted person. Second, the LDAA has consistently opposed the overturning of any verdicts because they “made promises to victims.” This is the same position they take when someone has been wrongfully convicted, even when exonerated by DNA.

When conservative justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote about non-unanimous juries in Ramos v., Louisiana, 590 U.S. __ (2020), one might have felt he was writing on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (founded by Thurgood Marshall, who later became the conscience of the U.S. Supreme Court). Justice Kavanaugh might have been surprised that the LDAA was so comfortable with their Jim Crow procedures which are so patently in violation of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.” And when the Court later left retroactivity to the state of Louisiana, this conservative body likely underestimated the unification of powers under the district attorneys.

It was only a decade ago when conservative Chief Justice John Roberts uttered his disbelief regarding Louisiana district attorneys’ flagrant violations of the Brady doctrine, which requires them to turn over evidence favorable to the accused. First came John Thompson’s famous case, when he was exonerated from Death Row, and then Juan Smith just a month later. In the first case, it was legendary DA Harry Connick’s contention that he hadn’t read a Supreme Court decision since law school. In the second case, Justice Roberts excoriated the state’s attorney, wondering if she even understood Brady (a half-century old case) at all.

One might wonder how the U.S. Supreme Court, and the Founding Fathers, would feel about the unification of powers that exist in Louisiana. If the LDAA’s bill passes as it is, there is a provision that bars any collateral attack, and blocks any appellate review. It is seen as a final judgment. It is unclear if the judiciary would see it the same way. Another half-century old U.S. Supreme Court case, Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 US 254 (1970), stands for the principle that administrative hearings need to be held to a proper standard of procedural due process. And the larger the thing at stake, the more stringent the review. In Goldberg, the interest at stake was welfare benefits. Here, the stake is someone’s freedom and their life. There can be nothing higher, but LDAA believes this hearing should not be reviewed—and wants that written in the law.

For many years, parole and revocations of parole were seen as “grace” extended by the Executive, and so could not be reviewed. Despite boards and hearings, the law provided no opportunity to appeal any unfairness, discrimination, or lack of due process. But along came Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 US 471 (1972), and then Gagnon v. Scarpelli, 411 US 778 (1973) (applying to probation revocation hearings), which refuted the concept of being in a “state of grace.” Where people have a liberty interest, they have a right to due process and equal protection.

Perhaps the LDAA and legislators intentionally drafted the bill to be a “final ruling” because final rulings can be appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. Doubtful, but that would be the likely next step in costly litigation. Someone would certainly file a petition for a writ of certiorari; and it is reasonable that the conservative court would be stunned by the brazen approach of a legal system run by district attorneys who have no term limits.

The only articulable defense of people languishing in prison based on Jim Crow juries is the inconvenience and challenge of new trials. And yet, rather than dispersing 1500 cases across 42 judicial districts in Louisiana, many of whom would likely negotiate a plea bargain, LDAA is content with filtering all 1500 into a 5-person panel to review the complete record and become both judge and jury. They have spoken of the costs to re-try people, and yet do not equate it with the costs for these potentially in-depth parole hearings and the likely litigation that follows the inevitable denials.

During COVID, when people were dying in jails and prisons and even the State Public Health Officer called for releases to allow more spacing in tightly-packed dormitories, the legislature (along with the LDAA and Sheriff’s Association) came up with a review panel similar to this proposal. They limited eligibility to several thousand people who were within 6 months of completing sentences on non-violent crimes. After all the objections, fewer than 20 people were released. Every one of those few thousand were ultimately released prior to the vaccine, and some of those granted “compassionate release” finished their sentences prior to the ruling.

The LDAA and Sheriffs are vehemently against releasing anyone a day earlier than forced to by law, and they have motivated legislators to join this position. This applies to quadriplegic patients, and people confined to beds or wheelchairs with terminal illnesses. Coincidentally, the federal court has also ruled that incarcerated healthcare falls below constitutional standards and violates the Americans with Disabilities Act. Given this resistance to releasing anyone with any conviction, it is impossible to imagine the LDAA representative voting to parole anyone who will basically need to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a miscarriage of justice occurred in their case. Realistically, they proved that years ago, when at least one juror voted to acquit. Or as VOTE member Ms. Darlene testified at the legislature: Four voted to acquit, but over the next few days, two got worn down by the others and conceded, just so they could finally go home.

These panels, if applying unanimity, should require a unanimous panel to keep someone in prison- rather than a unanimous panel to put them under the onerous conditions of parole.

Anyone looking for more evidence of how two people can see the same set of facts (or lack of facts) and come to different conclusions, need only glance at the heart of the State v. Reddick appellate briefs. In this case, where Reginald Reddick was convicted of second degree murder in 1997 despite two jurors ruling “not guilty,” and Mr. Reddick would like his conviction to be ruled unconstitutional.

First, take a read of how “the state” views this case:

Attorney General Jeff Landry’s office, joining in with the district attorney’s office to form the “state’s” position, makes Reginald Reddick’s case appear open and shut. Life without parole.

And yet… from Mr. Reddick’s brief:

Further:

Clearly, the State prosecutorial team is incapable of taking an unbiased view on any of these convictions, and would block every parole application that is filed. According to Attorney General Landry’s own brief, he also writes that “the state has never conceded that the non-unanimity rule is the product of racial animus.” And falsely claims “history cuts against making Ramos retroactive because Louisiana’s 1973 Constitutional Convention undoubtedly passed the non-unanimity rule for race neutral reasons.” Even if some officials are blind to racism, the fundamental unfairness of non-unanimous juries would also apply to all-white juries with a white defendant. And to the point, as the U.S. Supreme Court noted in Ramos:

[t]aking cognizance of discrimination and not curing it, cannot, as the State argues, cure the policy of its discrimination, either in intent of in impact. . . .The current scheme [adopted in 1973] continues to perpetuate the discrimination intended and adopted in 1898.” (citing State v. Maxie).

On Tuesday, the Louisiana Supreme Court will have a very basic decision to make. One appellate court ruled that unconstitutional verdicts cannot stand, and the Ramos ruling should be retroactive. Another appellate court ruled the opposite. The issue has been researched and debated across courts and in the community. 64% of voters, when presented with the issue for the first time in Louisiana history, said that conviction by Louisiana’s juries should be unanimous—just like the rest of the country.

Oral argument is at 2pm, tomorrow, May 11.

The community will be both in the courthouse and on the courthouse steps. The arguments may also be viewed live: https://livestream.lasc.org/